Greetings from Element's backend/SRE team, who run the matrix.org homeserver on behalf of the Matrix.org Foundation.

Recently users of the matrix.org homeserver began seeing problems where rooms would simply stop working. Operations such as sending a new message, or joining the room as a new member, would fail for mysterious reasons. Where an error message was shown at all, it tended to be something cryptic like "No create event in auth events".

After a couple of weeks of hard work by a team of Element staff including backend developers and systems engineers, we were able to repair almost all of the affected rooms. Although we're still investigating exactly what went wrong and checking that everything is now working as it should, we'd like to share some details about what we know and the work we've done to date.

We'll be diving into some quite technical details. Hopefully you'll find it interesting learning a bit about how Synapse works, how Postgres works, and the work we sometimes find ourselves doing to keep the matrix.org homeserver running.

🔗TL;DR

Let's start with a high-level summary.

The matrix.org homeserver is backed by a large PostgreSQL database instance. Parts of an index on one of tables in this database had become corrupted. We are unsure exactly what caused this corruption, but believe it happened at least a year ago, and likely significantly longer.

The nature of this corruption was such that it had little or no effect at first. However, a background maintenance task which removes old, unreferenced data from this table recently started working on the corrupted region. Due to the corrupt index, the maintenance task incorrectly removed active data from the table, in effect corrupting rooms.

Having identified the problem, we rebuilt the corrupted index, and then restored the data that had been incorrectly removed, from database backups.

🔗Initial investigations, or "what exactly is a state group?"

We were first alerted to the problem via a bug report from a user, and similar reports in public Matrix rooms and other social media. As more anecdotal reports came in, we started to investigate what was going on.

To understand what we found, you'll need to understand what we mean by a "state group".

As most readers probably know, Matrix allows applications to associate "state" with a room. In contrast to "message" events which are normal messages that fit at one particular point in the timeline, state sticks around, visible to all, until it is replaced. One example of state is a user's room membership — whether or not they are currently a member of that room. Another example is m.room.name, which, as the name implies, holds the room's name.

Yet another type of state is the "create event": this is the very first event that happened in a room. The create event is somewhat special in that it can never be changed, but we still always expect it to be part of the room state.

Obviously, the state of a room changes over time. What may be less obvious is that a homeserver often needs to know what the state of a room was at some point in the past, to answer questions such as "should this user be allowed to see this event" or "should I accept this event that has been sent to me over federation from another homeserver". Whilst in theory we could figure out what the state was at any given point in history by replaying each event that happened in the room before that point, that would be extremely computationally intensive. So in practice, homeservers end up storing what amounts to a snapshot of the room state at each historical event.

Of course, regular events don't change the state of the room, so there is no point actually storing the state at each of those events. So, at last we can understand what a "state group" is: Synapse groups together a set of events in a given room, where the state in that room remained unchanged. In other words, a run of m.room.message events (normal room messages) will likely all share the same "state group". Once somebody changes the room state (for example, by joining the room), we'll start a new state group, and subsequent events will be part of that new state group.

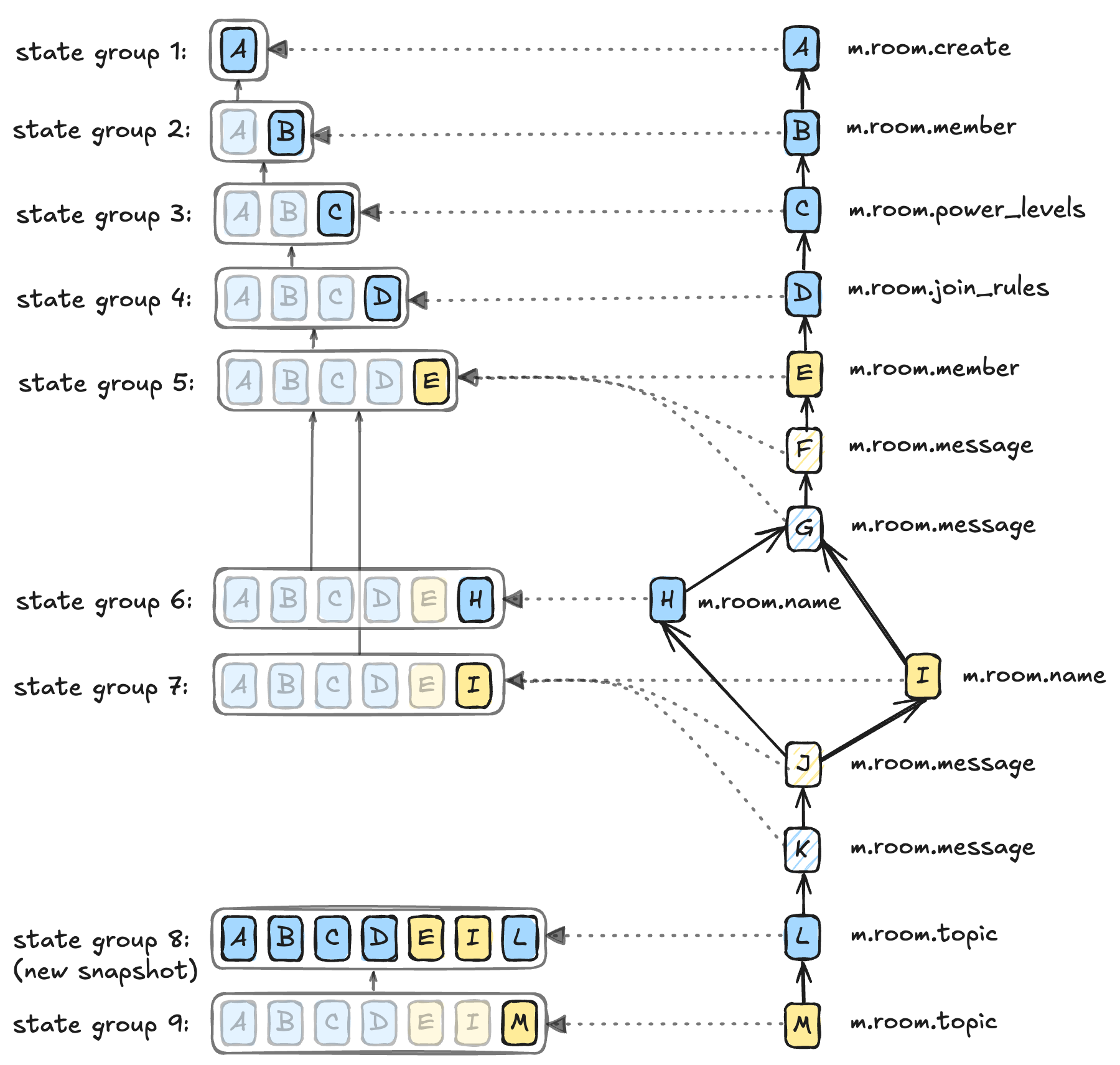

The diagram below illustrates this. Blue creates a new room, and Yellow joins. The first few events each change the state of the room, meaning that each new event goes into a new state group. But events F and G are regular messages, meaning they don't change the state of the room. The room state after each of events E, F and G is the same, so they can all be in state group 5.

Things get a bit more complicated at H and I: both Yellow and Blue try to change the name at the same time, so the state after H includes H and the state after I includes I. The state resolution algorithm determines that I ends up "winning", so the state after J includes I and not H, meaning that J (and K) can share state group 7 with I.

Now, when we started investigating the rooms where people had reported problems, we found clear signs of corrupted state groups. For example, the state in some of the state groups in affected rooms was completely empty. As I said earlier, the room's create event is always part of the state of a room, and it can never change, so finding state groups whose state does not at least include a create event was a big red flag.

This also gives a clue to the meaning of that error I mentioned earlier: when we decide whether to accept an event into the room, we check the state of the room. One of the things we check for is the presence of a create event: "No create event in auth events" means Synapse rejected the new event because there was no create event in the room state.

There's one more wrinkle we'll need to understand about state groups. As you can see in the diagram above, most state groups only differ very slightly (typically by a single piece of state) from the previous state group in the same room. Storing a complete snapshot of the state every time the state in a room changes would be very expensive in terms of storage. So instead, Synapse normally just stores the difference from an earlier state group; then, to stop lookups becoming too expensive, we store a complete snapshot every 100 state groups or so.

Again, you can see that "compression" technique at play in the diagram above. Most state groups have a grey arrow representing the link to the previous state group, meaning that each state group only needs to store the delta from the previous state group (shown in bold whilst those states implied by the "previous" link are greyed out). State groups 1 and 8 are stored as complete snapshots.

Synapse stores all this data in its database: the event_to_state_groups table tells us which state group each event is in, state_groups_state stores the actual state snapshot or delta for that state group, and state_group_edges gives us the previous state group for delta-stored state groups.

🔗The hunt for suspects

Thanks to the way Matrix works, once Synapse has created a state group, we very rarely ever have to change it. (If more events arrive, they may be assigned to an existing state group, but the state group itself, and the room state for that state group, remain unchanged). The only exceptions are:

- the state compressor, which rewrites state groups so that they can be stored more efficiently.

- purge operations, where all or part of a room's history is removed from the database, making the corresponding state groups redundant.

- a cleanup job which removes state groups which were created but never used.

... and of course, the creation of the state group in the first place.

At least that gave us a place to start looking, but since we hadn't made any changes to those areas of the code recently, we were still at a bit of a loss.

The state compressor was easy to rule out, at least, since it runs as a separate process and we were certain it wasn't running on matrix.org.

As a precaution, we temporarily disabled the cleanup job that removes redundant state groups. We couldn't figure out how it could cause the problem, but better safe than sorry, and disabling it would just mean we used a bit more disk space for a while.

🔗More evidence comes to light

Our next step was to try and figure out when the problem started. Searching the logs for one Synapse process gave some clear, and worrying, results:

- 2025-06-24: 0 results for “No create event”

- 2025-06-25: 0 results for “No create event”

- 2025-06-26: 0 results for “No create event”

- 2025-06-27: 48 results for “No create event”

- 2025-06-28: 1100 results for “No create event”

- 2025-06-29: 3610 results for “No create event”

- 2025-06-30: 6902 results for “No create event”

So, we double-checked for changes that had been made around 27th June, and still didn't find anything. We considered rolling back Synapse to an older version, but since we couldn't figure out what had changed, we didn't know how far we would have to roll back.

What's more, we found state groups that must have been fine initially (say, on 2025-06-29) were now corrupt: in other words, this confirmed that the problem wasn't that we were creating new, invalid state groups, but there was a process somewhere in the system that was corrupting existing state groups.

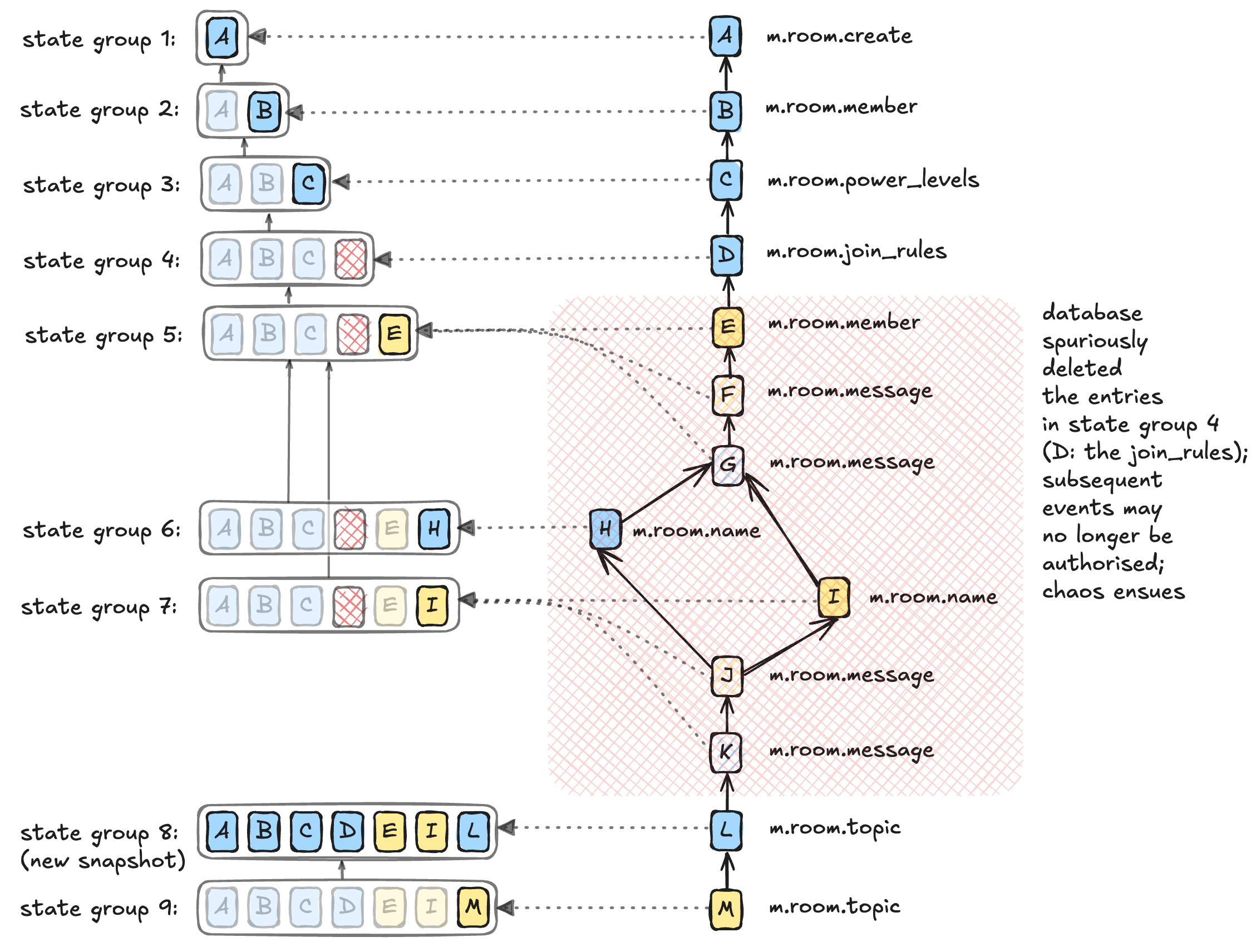

The diagram below illustrates the problem. The state in state group 4 has been corrupted, meaning that that state group (and state groups 5, 6, and 7 which all reference it) are now missing an important part of the room state, and events will not be authorised.

🔗Some remedial steps

Now that we knew we were dealing with data loss, it seemed likely that we would need to restore data from backup, so started the process of restoring the database backup from 26th June into a new Postgres instance hosted in Amazon EC2. The restore process takes several hours, so we wanted to get it started. On the other hand, it would leave the Matrix Foundation an EC2 bill of hundreds of USD per day for an EC2 instance large enough to host the database!

We also set up a guard against further corruption: we added a Postgres "constraint" which would reject any SQL queries which attempted to delete the state from a state group while that state group was still in use.

🔗A culprit emerges

By this point, it was the morning of 3rd July. The cleanup job had been disabled for 24 hours, and we hadn't seen any further corruption. Now that we had the protective constraint in place, we decided to re-enable the cleanup job, and see what happened. Almost immediately, we could see that the cleanup job was hitting the constraint. From the Postgres logs:

2025-07-03 12:30:38.250 UTC [matrix background_worker1] ERROR: Deleting state_groups_state row when it still exists in state_groups_edges: prev_state_group = 963361509

... meaning it was trying to delete the state for state group 963361509 while that state group was still in use. The Synapse logs, meanwhile, suggested it was actually trying to delete completely different state groups. Was it a bug in Synapse? Or the Python Postgres driver?

We spent a while narrowing down the problem, even resorting to tcpdump to see what was happening between Synapse and the database. With tcpdump, we could see DELETE queries being made, but none which would affect state group 963361509. Maybe this was actually a bug in PgCat, which we use to pool Postgres connections? Or even in Postgres itself?

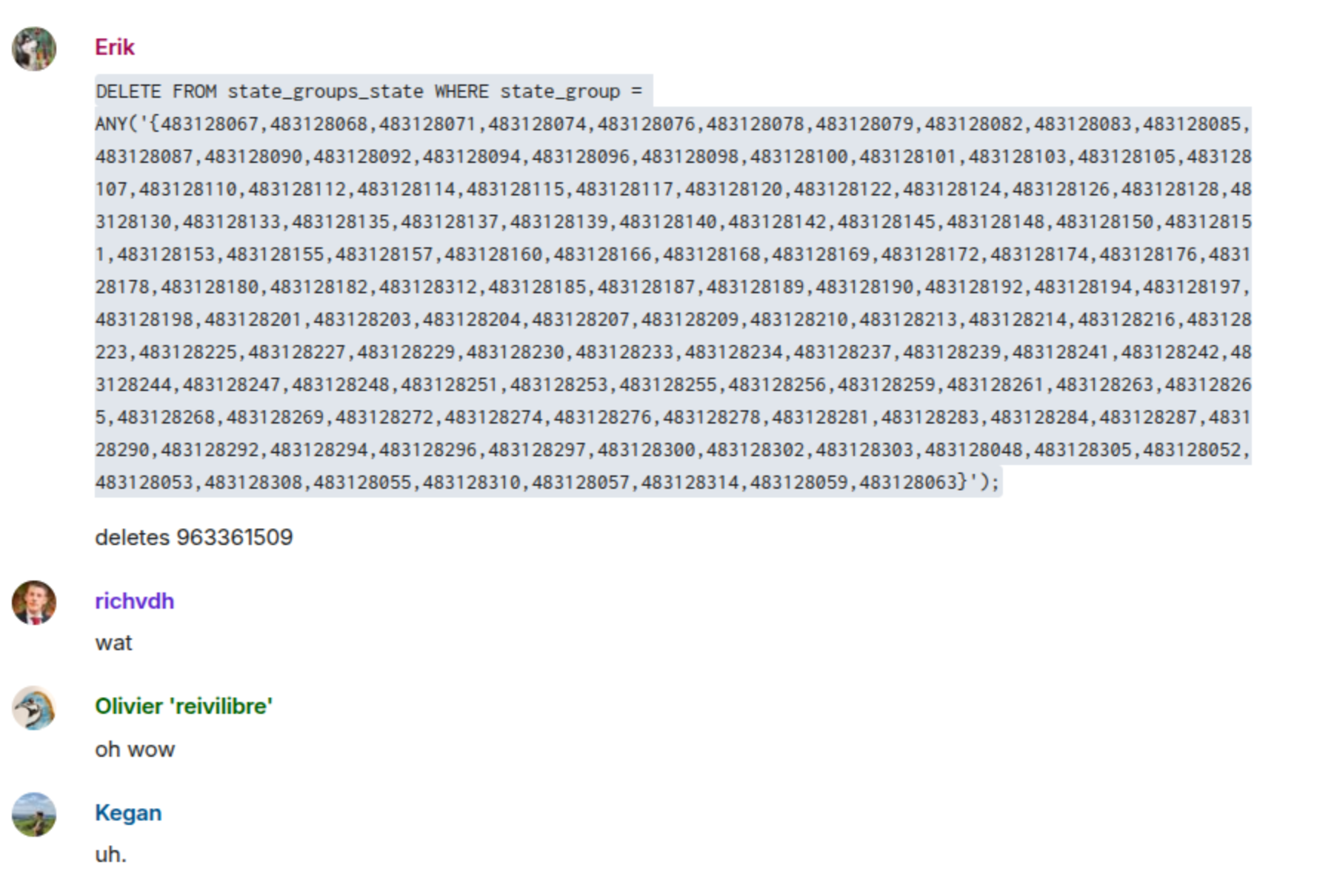

We tried replaying the query that tcpdump had captured. Here's a screenshot from our ops room:

Oh wow indeed. That shouldn't happen. We narrowed the problem down to one particular state group: 483128098. What happens if we just try and read that state group from the database?

matrix=> SELECT state_group, room_id FROM state_groups_state WHERE state_group = 483128098;

state_group | room_id

------------+----------------------------------------

483128098 | !XtFbidoIcAVPuQtXcG:matrix.org

963361875 | !IvVovpFpWhKsKMCGCO:irc.snt.utwente.nl

483128098 | !XtFbidoIcAVPuQtXcG:matrix.org

(3 rows)

Oh dear. Once your database starts returning nonsense results, you're going to be in for a bad time.

What it meant here was that, although the cleanup job was (correctly) trying to clean up state group 483128098, Postgres would also delete the data for state group 963361875. Suddenly things started to make sense: rooms were getting corrupted by cleanup jobs for completely unrelated rooms.

We've encountered Postgres index corruption before, and this matched the symptoms perfectly. In short: the index entries for state group 483128098 point to the wrong place in the main table data (the "heap"). So, if we did a query that Postgres could answer by just looking at the index, we'd get plausible-looking results:

matrix=> SELECT state_group, type FROM state_groups_state WHERE state_group = 483128098;

state_group | type

------------+--------------

483128098 | m.room.member

483128098 | m.room.member

483128098 | m.room.member

(3 rows)

... but as soon as Postgres had to look at the heap, it would return nonsense, as above.

🔗Give it to me straight, doc

The good news, such as it was, was that we could now be reasonably certain that other homeservers would not be affected: this was data corruption on the matrix.org Postgres instance.

On the other hand, we had no idea how extensive the corruption was, when it had happened, or if it was still happening.

We did several things to try to assess the damage.

The first thing to check was whether both Postgres instances had the same problem. (We replicate all our data to a warm standby server using streaming replication so that we can fail over rapidly in the event of a hardware failure.) As far as we could tell, both servers had identical corruption.

Secondly, we wrote a script which sampled the state_groups_state table to look for corruption. It told us that the problem was worryingly large: millions of state groups were affected. But for some reason, it only seemed to affect state groups in the range 147M - 541M. (State group 541M was created in January 2021. As of July 2025, we're now up to 1040M.)

We also ran pg_amcheck on the affected index. This is a tool that forms part of the Postgres distribution, and it checks for inconsistencies in all or part of a database. It took a while, but didn't return any problems. This mostly told us that amcheck couldn't detect this sort of corruption, but one thing it checks is that all rows in the table also appear in the index; so now we knew that we weren't missing any index rows — we just had extra ones.

Meanwhile, we tried reaching out to the helpful folks on the pgsql-general mailing list. We figured if anyone knew what could have caused this, they would.

The final thing we did at this point was to take a look at the actual index data with pageinspect, to see if there were any clues there. It didn't really tell us anything we didn't already know (i.e., that the index rows were pointing at the wrong place in the heap), but it was interesting to check out the structure of the index.

🔗A deeper dive into Postgres indexes

On the morning of 4th July, our backup from 26th June at last finished restoring. That meant two things: first, we could check if it had the same index corruption as our primary and secondary servers (it did), and secondly, we could start to think about how to repair the damage.

We noticed something else interesting, though. On the production servers, some index entries pointed to state groups which didn't yet exist on 26th June:

-- On the production database

matrix=> SELECT state_group, type, ctid FROM state_groups_state WHERE state_group = 353864583;

state_group | type | ctid

-------------+---------------------------+----------------

353864583 | m.room.member | (39060361,12)

1034753774 | m.room.member | (264925234,54)

1034753810 | im.vector.modular.widgets | (264925240,54)

1034753803 | m.room.member | (264925252,54)

1034753803 | m.room.member | (264925252,55)

(5 rows)

(ctid, or "current tuple ID" is Postgres's internal identifier for a row in a table: the format is a page number, followed by an offset within that page. We'll return to ctids in a minute.)

Those state groups (1034753774 etc.) were only created on 3rd July, so clearly the backup will look different. Indeed:

-- On the restored backup

matrix=# SELECT state_group, type, ctid FROM state_groups_state WHERE state_group = 353864583;

state_group | type | ctid

-------------+---------------+---------------

353864583 | m.room.member | (39060361,12)

(1 row)

Did that mean that the corruption was ongoing? Time for another look with pageinspect.

As with most Postgres indexes, this one is a B-Tree. To find a specific entry, you start at the "root" of the tree (a single page which covers the whole table, but with very coarse index entries: there might be one sub-page for all the A's, for example, and another for all the B's), and work down the tree until you get to the right "leaf" page.

On our restored backup, we manually walked the tree to find the leaf index pages for state group 353864583. Turned out, there were several pages of entries: it seems like, at some point in the past, this state group had lots of state associated with it. Anyway, the interesting page was this:

-- On the restored backup

matrix=# select ctid, left(data, 77) as data from bt_page_items('state_groups_state_type_idx', 192904826);

ctid | data

----------------+-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(264925236,41) | 87 8b 17 15 00 00 00 00 1d 6d 2e 72 6f 6f 6d 2e 6d 65 6d 62 65 72 35 40 66 72

(264925234,54) | 87 8b 17 15 00 00 00 00 1d 6d 2e 72 6f 6f 6d 2e 6d 65 6d 62 65 72 4b 40 66 72

(264925235,54) | 87 8b 17 15 00 00 00 00 1d 6d 2e 72 6f 6f 6d 2e 6d 65 6d 62 65 72 47 40 66 72

(3 rows)

Being a leaf index page, the ctid points to the actual row in the heap. This is an index on (state_group, type, state_key), so the data here is:

- a little-endian 64-bit representation of

353864583 - a length/flags byte (

1d=> 13 bytes of uncompressed text) - the event type (

m.room.member) - another length/flags byte

- the

state_key: a user ID, which I've truncated in the above for brevity and privacy.

The point is, even in the backup, we have index rows pointing to heap tuple (264925234,54). And what is at that heap tuple?

matrix=# SELECT * FROM heap_page_items(get_raw_page('state_groups_state', 264925234));

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid | t_data

----+--------+----------+--------+--------+--------+----------+--------+-------------+------------+--------+--------+-------+--------

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | | | | | | | | | |

(1 row)

Nothing at all. That tuple doesn't exist. It's just empty space in the table data.

Finally, we can understand a bit about what's happened here. The corruption is not ongoing. Rather, the index was already corrupt at the time the backup was taken, but the index rows point into empty space -- and apparently Postgres ignores such index rows.

Then, on 3rd July, that empty space got used for state group 1034753774, meaning that the index entry for state group 353864583 now points to the data for state group 1034753774.

This tells us something else interesting: this corruption could have been there for months or years, without anyone noticing. It was only once Postgres started populating that bit of table space that any problem would have been observable.

So why was the index entry pointing at empty space? That's a great question, and something we spent a long time discussing. Presumably, at some point in the past, we used to have lots of entries in state_groups_state for state group 353864583. Then, most of these entries were removed (likely by the state compressor), causing a bunch of free space to be created in the table data -- but for some reason, the index entries for those rows didn't get correctly cleaned up, leaving them dangling.

🔗Repairing the damage

We now had enough information to start to get things working again.

The first priority was to get Postgres back to a consistent state. That meant rebuilding the index, which in itself wasn't trivial, given the index takes up over 4 TB — but we had just enough spare disk, so we set the reindex going overnight.

Next, we needed to repair any state groups which were incorrectly modified by the cleanup job due to the corrupt index. To do this, we considered the range of state groups that the cleanup job had been working on, and wrote a script which queried each of those state groups on our restored backup, noting down the targets of any bogus data: this was the list of potential victims of incorrect cleanup.

We then cross-referenced that list of potential victims against the production database, checking for state_groups_state entries which had been removed but where the state group was still in use: this gave us the actual victim list. Each of those victims had to be re-inserted into the production database.

We started those scripts running on 5th July, but due to the amount of data involved, it took nearly a week before we were able to announce on 11th July that the majority of rooms were repaired.

🔗Assessing the root cause

So, what went wrong to cause those index pages to get corrupted? The short answer is, we don't know.

First, some timeframes. We know for certain that corruption happened after January 2021 (or at least, that corruption was still ongoing at that point), since it affected state groups created at that time. And we know that it happened before July 2025, since corruption was present in the backup from the end of June. It's hard to be any more certain than that.

The one thing we can be sure it's not is a bug in Synapse or PgCat: there is no way that an application should be able to cause internal corruption within a Postgres database.

One possibility is a Postgres bug, but Postgres is an extremely robust piece of software, and the Postgres team treats corruption bugs extremely seriously. We were using Postgres 10.12 in January 2021, and we've looked through the Postgres release notes for every version since then, and not found any bug fixes that would fit this pattern.

It's worth noting that Postgres relies heavily on its underlying filesystem, as well as the device drivers and hardware, to behave correctly: in particular, if the filesystem claims that data has been persisted, it really has been persisted. Problems in this area are far from unknown — back in 2018, the Postgres team discovered that their 20-year-old assumptions about how fsync worked were incorrect (wiki page, FOSDEM presentation). But the fixes to that were backported to Postgres 10.7 so that problem can't explain this corruption.

So that really leaves kernel or disk firmware bugs, and hardware failures. Our filesystem is nothing fancy, just ext4, and we're using stock Debian kernels. Some sort of hardware problem seems like the most plausible cause. We're somewhat surprised that hardware failure would cause extensive damage to a single index, whilst apparently leaving all other data intact, but it's at least possible.

For the curious: our current generation of database servers run Linux kernel 6.1, and each server uses eight 15TB Intel NVME SSDs in a RAID10 configuration to give us 64TB of storage. The previous generation (retired in November 2023) used 8TB SSDs with LVM and no RAID, on Linux 4.19. Of course, we have checked fsck, smartctl and mdadm for any errors on the current disks: none have shown up.

There was a disk failure on the primary database server in October 2021, which caused us to fail over to the secondary, so it's conceivable that the dying disk lost some writes, though it would have to have been doing so for a while for the corruption to have made it onto the secondary. We're not entirely satisfied with this explanation.

If you've got any ideas, let us know!

🔗Conclusions

Incidents like this happen from time to time when running software services, particularly relatively large scale ones like the matrix.org homeserver. They are impossible to plan for and often, as in this case, take significant time and effort from people who would otherwise be developing features or fixing bugs.

We know that there are plenty of users out there who will have been affected by the problem, and found themselves unable to communicate as a result. We very much share your frustration, and we'd like to apologise for the disruption to service.

With that said, we're glad that we were able to get to the bottom of most of the problem, and get the lost data restored within a relatively short time. If nothing else, hopefully this blog post will be of use to future generations faced with Postgres index corruption!

The Foundation needs you

The Matrix.org Foundation is a non-profit and only relies on donations to operate. Its core mission is to maintain the Matrix Specification, but it does much more than that.

It maintains the matrix.org homeserver and hosts several bridges for free. It fights for our collective rights to digital privacy and dignity.

Support us