This Week in Matrix 2022-02-04

04.02.2022 00:00 — This Week in Matrix — ThibMatrix Live 🎙

Dept of oh hey it's FOSDEM

TravisR says

We've got a devroom. check it out. https://fosdem.org/2022/schedule/track/matrixorg_foundation_and_community

And let me add

You can join our devroom at #matrix-devroom:fosdem.org to watch all the talks, and our stand at #matrix-stand:fosdem.org

Dept of Spec 📜

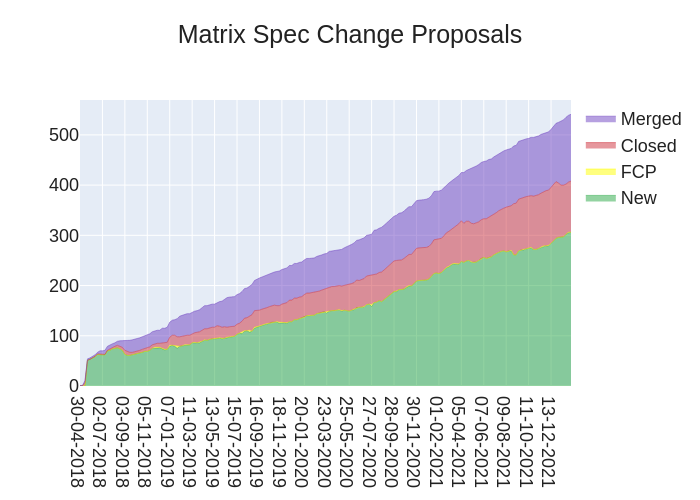

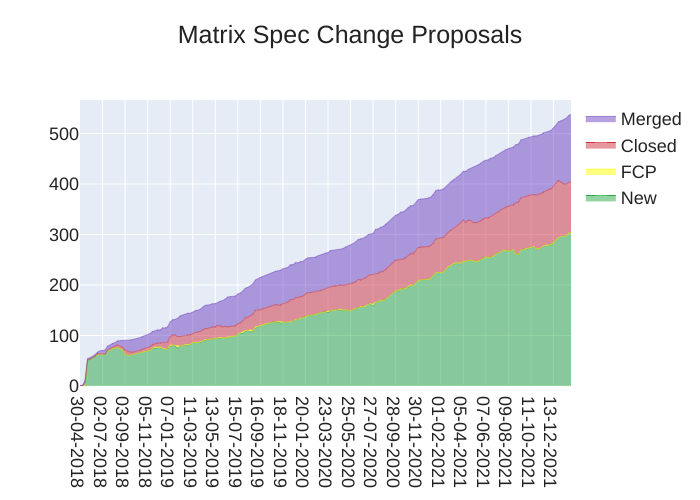

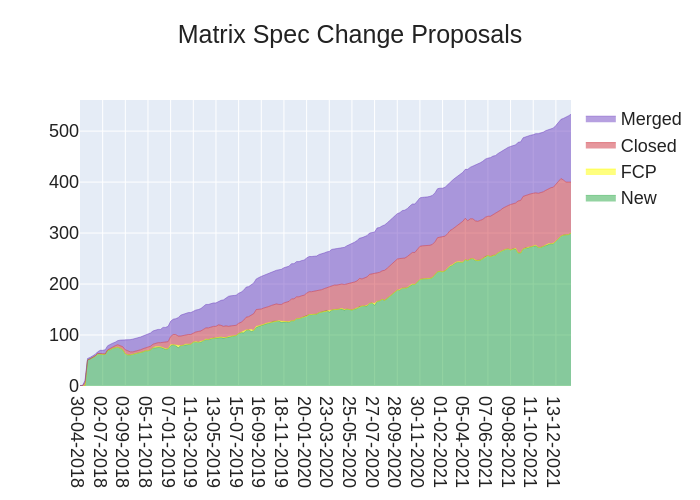

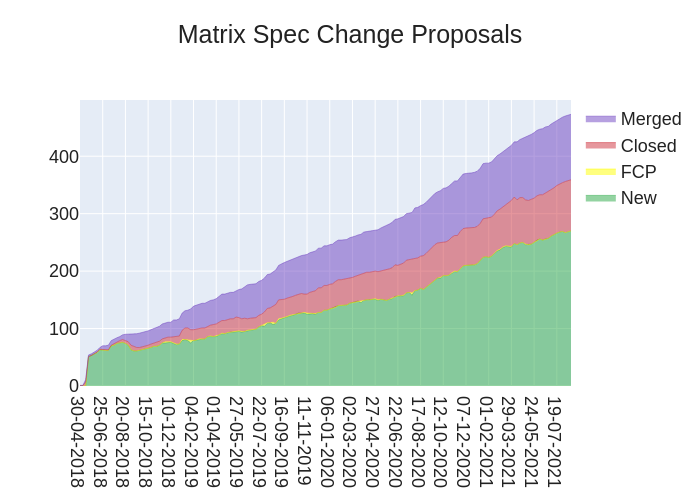

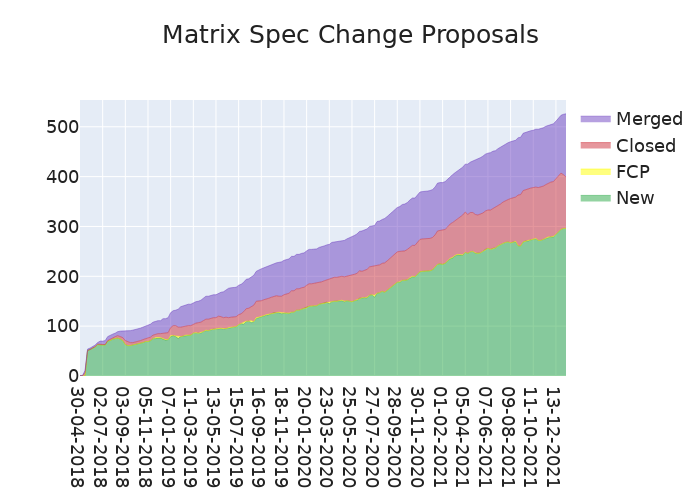

anoa announces

Here's your weekly spec update! The heart of Matrix is the specification - and this is modified by Matrix Spec Change (MSC) proposals. Learn more about how the process works at https://spec.matrix.org/unstable/proposals.

MSC Status

New MSCs:

- WIP: MSC3706: Extensions to

/_matrix/federation/v2/send_join/{roomId}/{eventId}for partial state- MSC3700: Deprecate plaintext sender key

MSCs with proposed Final Comment Period:

MSCs in Final Comment Period:

- No MSCs are in FCP.

Abandoned MSCs:

Merged MSCs:

Spec Updates

Matrix v1.2 has landed! 🥳 Read the official announcement blogpost and check it out over at https://spec.matrix.org/v1.2/. This release includes headlining features such as Spaces, room versions 8 and 9 which bring restricted join rules, as well as the new Matrix URI scheme.

I'd also like to point out that v1.2 released on 2/2/2022 :)

Otherwise, thank you to aaronraimist and devonh from the community for their fixes to the spec's text that merged this week. They are highly appreciated!

Random MSC of the Week

The random MSC of the week is... MSC3051: A scalable relation format!

This MSC proposes to pave a way to allowing relating an event to multiple other events, which unlocks some additional use cases. Go check it out if you're interested in extending Matrix's capabilities even further!

Dept of Servers 🏢

Synapse (website)

Synapse is the reference homeserver for Matrix

callahad announces

Synapse 1.52.0rc1 is out, but honestly, we're just all hands on deck for FOSDEM tomorrow! As a reminder, members of the Synapse team will be giving a couple of talks during at the event:

Events for the Uninitiated by Shay at 10:10 UTC

Beyond the Matrix: Extend the capabilities of your Synapse homeserver by Brendan at 15:40 UTC

Be sure to check out all of the talks in the Matrix.org Foundation & Community devroom or visit the Matrix stand for more freeform discussion — we'll see you there!

Dendrite (website)

Second generation Matrix homeserver

neilalexander says

Today we've released Dendrite 0.6.1 which contains a number of fixes and improvements. This release includes the following changes:

- Roomserver inputs now take place with full transactional isolation in PostgreSQL deployments

- Pull consumers are now used instead of push consumers when retrieving messages from NATS to better guarantee ordering and to reduce redelivery of duplicate messages

- Further logging tweaks, particularly when joining rooms

- Improved calculation of servers in the room, when checking for missing auth/prev events or state

- Dendrite will now skip dead servers more quickly when federating by reducing the TCP dial timeout

- The key change consumers have now been converted to use native NATS code rather than a wrapper

- Go 1.16 is now the minimum supported version for Dendrite

- Local clients should now be notified correctly of invites

- The roomserver input API now has more time to process events, particularly when fetching missing events or state, which should fix a number of errors from expired contexts

- Fixed a panic that could happen due to a closed channel in the roomserver input API

- Logging in with uppercase usernames from old installations is now supported again (contributed by hoernschen)

- Federated room joins now have more time to complete and should not fail due to expired contexts

- Events that were sent to the roomserver along with a complete state snapshot are now persisted with the correct state, even if they were rejected or soft-failed

Spec compliance, as measured by Sytest, currently sits at:

- Client-server APIs: 65%

- Server-server APIs: 94%

As always, you can join us in #dendrite:matrix.org for Dendrite discussion and announcements.

Conduit (website)

Conduit is a simple, fast and reliable chat server powered by Matrix

Timo ⚡️ says

Hey everyone, this evening we will finally release the next Conduit version: v0.3

If you have questions about anything, come and ask us in #conduit:fachschaften.org

We have managed to get a lot of features and improvements into this release, here are some of the most exciting ones:

Feature: Support server ACLs !248

Feature: RocksDB Database Backend !217

Feature: Database backend selection at runtime !217

Feature: Report users to homeserver admin !218

Feature: Creation of Spaces (exploring spaces is not supported yet) !220

Feature: Enable voice calls (requires configuring a TURN server) !208

Feature: Lazy loading for much faster initial syncs !240

Improvement: Batch inserts for events !204

Improvement: Significantly faster state resolution !217

Improvement: Reuse reqwest client !265

Thanks to everyone who supports me on Liberapay or Bitcoin!

Homeserver Deployment 📥️

Dendrite Helm (website)

This chart creates a polylith, where every component is in its own deployment and requires a Postgres server aswell as a NATS JetStream server.

Till F. reports

Hi TWIM followers :)

dendrite-helm is an experimental Helm Chart to deploy a polylith/monolith Server.

After last weeks release of Dendrite 0.6.0, I finally updated my Helm Chart to finally reflect that.

Changes:

- Versioned releases (no more

latestdocker tags or such)- locmai added dependencies (NATS JetStream, Postgres)

- Update README (helm-docs)

Special thanks to locmai, who added the missing dependencies!

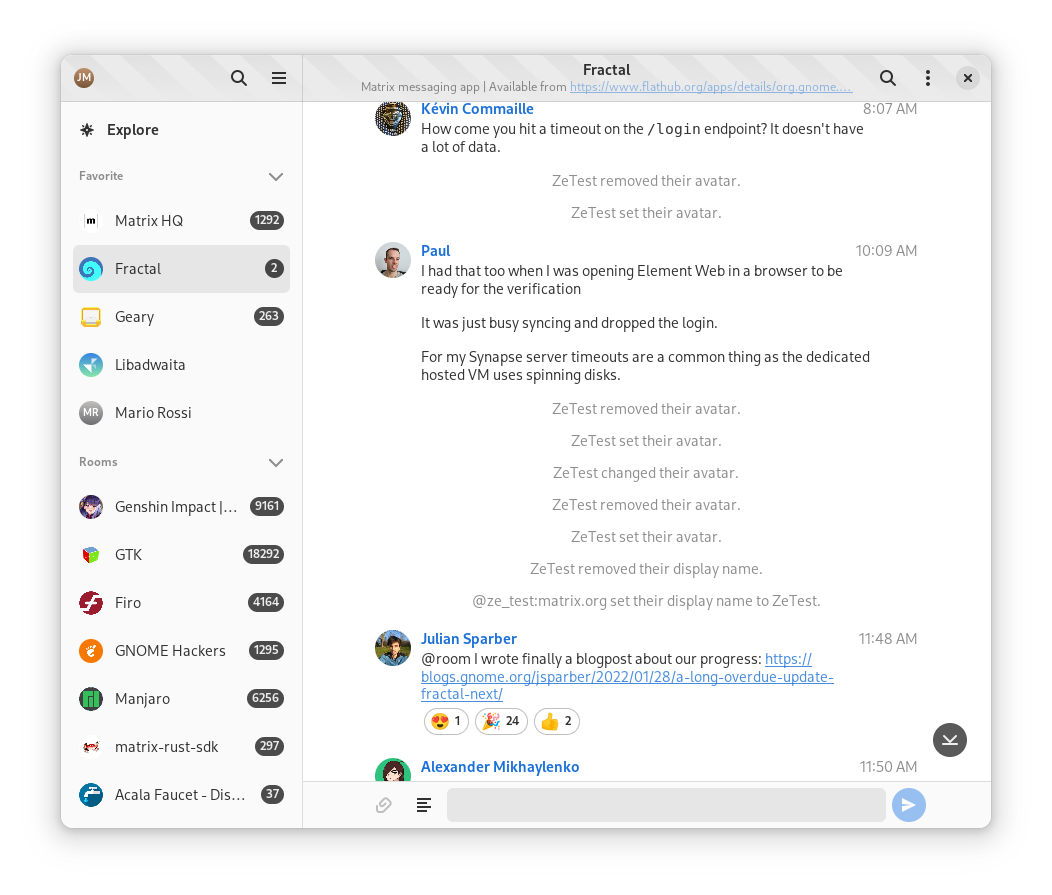

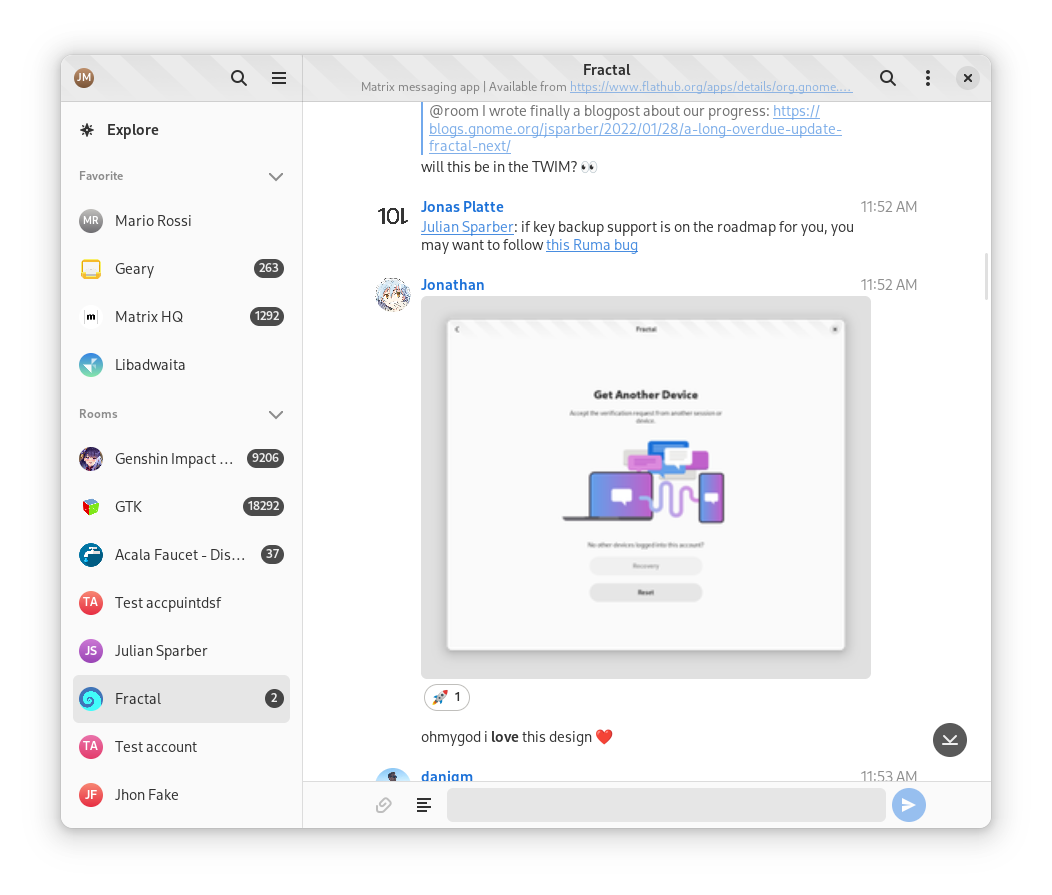

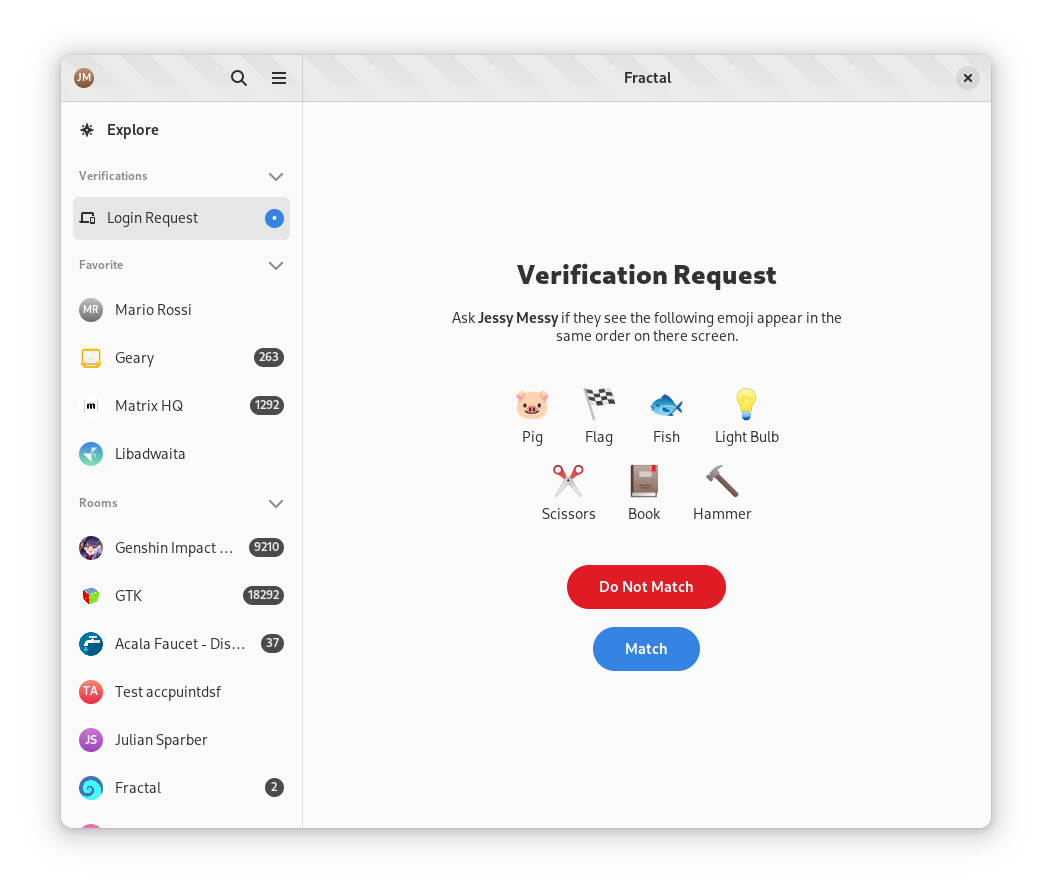

Dept of Clients 📱

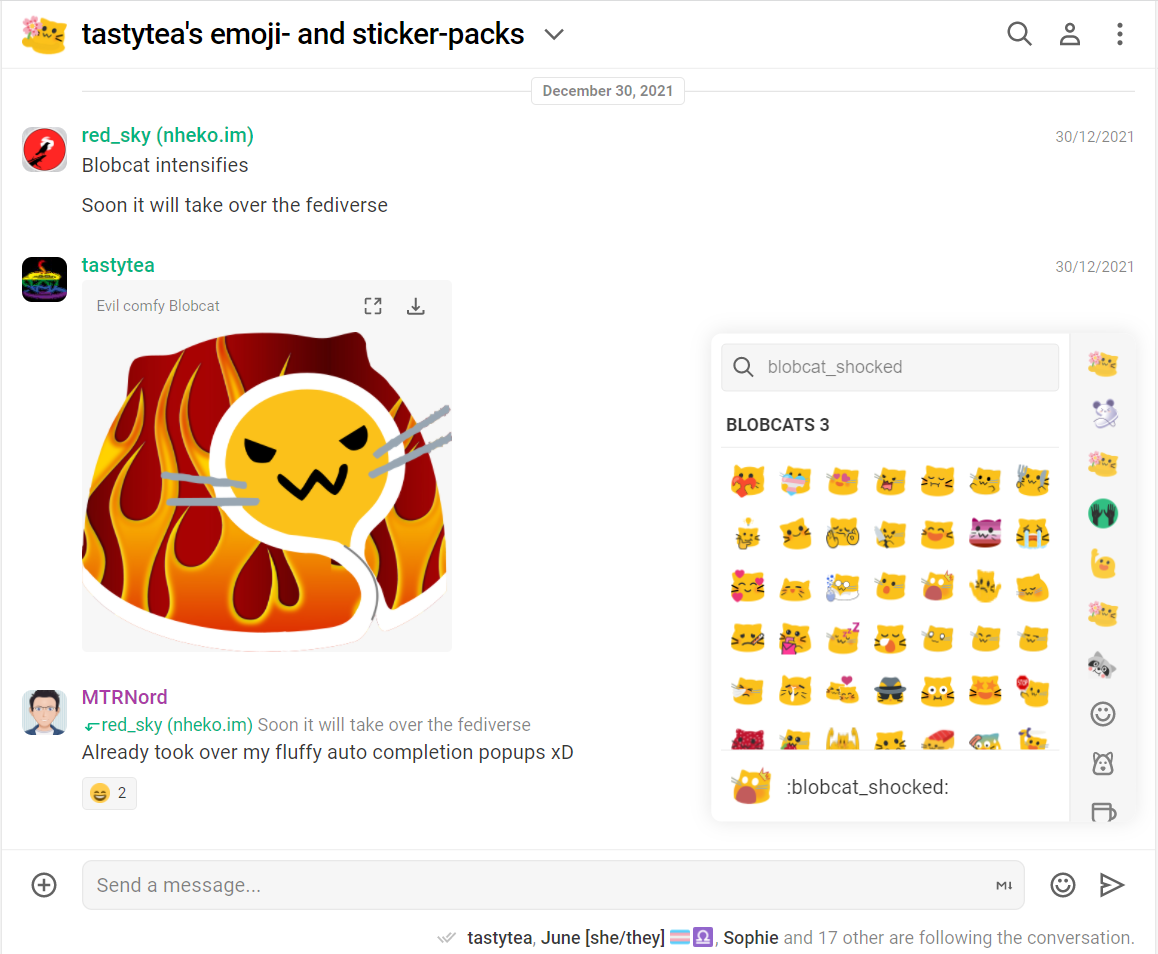

Nheko (website)

Desktop client for Matrix using Qt and C++17.

Nico reports

It's FOSDEM! Don't forget to checkout my 5 min ramble about custom stickers and emotes in Matrx: https://fosdem.org/2022/schedule/event/matrix_custom_stickers/

In preparation for FOSDEM, I've also been working on some goodies so that you can participate using Nheko in a limited manner:

- Previews for rooms are now fetched for spaces using the hierarchy API

- Widgets for the talks should be shown below the topic as links

While this isn't grand, it should be good enough for some to participate using Nheko. You will need the latest master (some commits aren't even pushed at the time of writing!), but if you are just watching, this should give you an easy way to fetch the talk link for each room. You will still have to watch the actual talk in your browser though.

LorenDB also added a big, fat, red offline indicator. If your server dies because of FOSDEM, now Nheko will tell you.

I hope you all will have a great time and I hope I see you around!

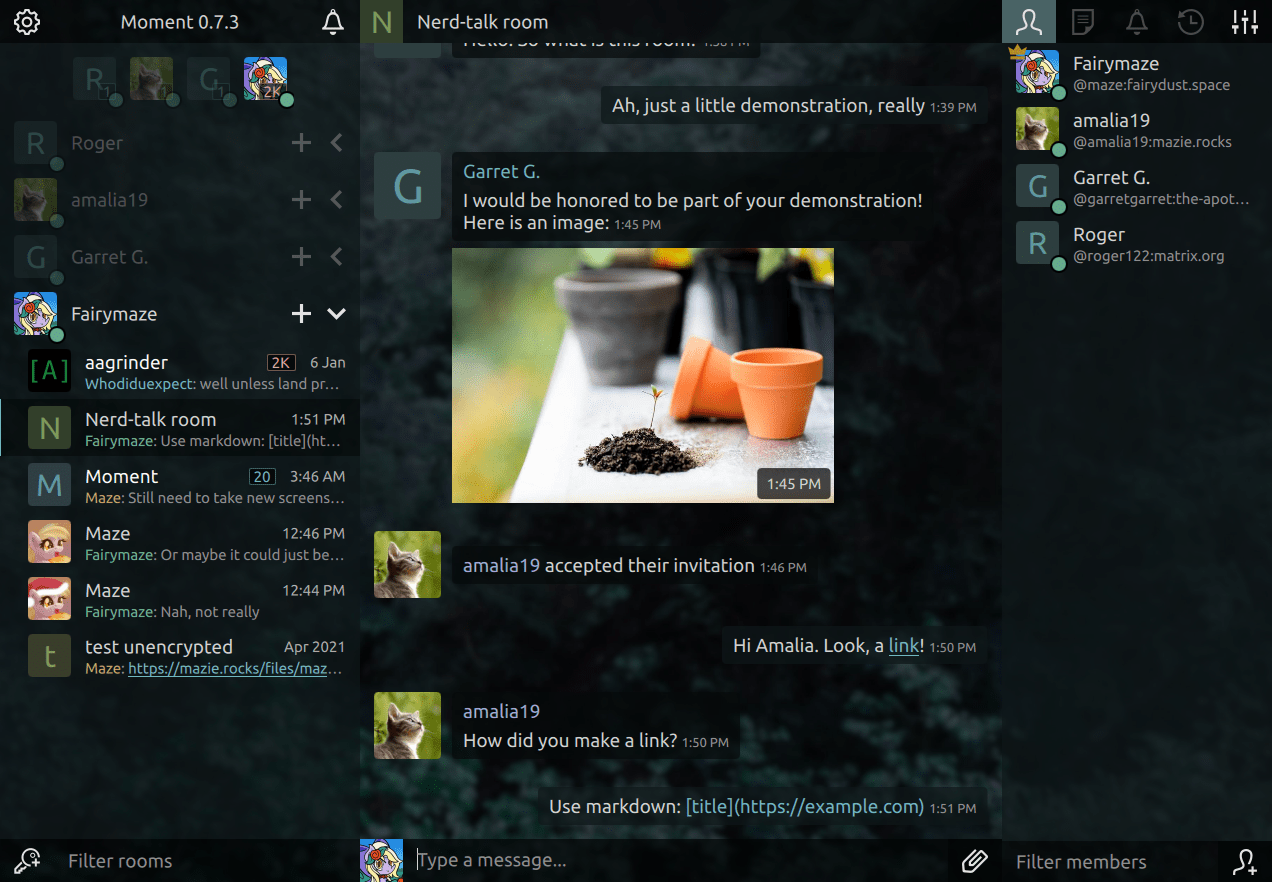

Moment (website)

A Matrix client; forked from Mirage.

@maze:mazie.rocks announces

Releasing Moment, a fork of Mirage! In case you missed out on Mirage, here's what this is:

- A fancy QML + Python client aimed at power users

- Keyboard bindings for almost everything

- Very customizable, with ability to adjust any keybinding/functionality

- A multi-account client

- Adjusts to any screen size

After 6 months of inactivity on the Mirage project, Moment brings it back to life. We have fixed some important issues and will continue to maintain Moment!

🏠 Matrix room: #moment-client:matrix.org

📁 Repo: https://gitlab.com/mx-moment/moment 🌐 Website: mx-moment.xyz 🔍 Differences between Mirage and Moment

🛠 Install Moment from source 📦 Install Moment from Flatpak ⛰ Install Moment on Alpine Linux

Hydrogen (website)

Hydrogen is a lightweight matrix client with legacy and mobile browser support

Bruno announces

🎺 We've released Hydrogen 0.2.24 and 0.2.25 with session backup writing and some bug fixes! From now on you shouldn't need to have another client running along hydrogen for keys to be written to the key backup!

Bruno adds

We've also just released 0.0.5 of the

hydrogen-view-sdkwith very early support for registration and exporting more symbols.

Element (website)

Everything related to Element but not strictly bound to a client

Danielle reports

Welcome to another week of TWIM at Element! Here’s our updates:

Polls and Location Sharing

- Polls is now out of labs, and available in the composer for all users with the latest app versions.

- Location sharing is also now available on the mobile apps. For now you will need to enable it in settings in order to see the composer icon and send your location.

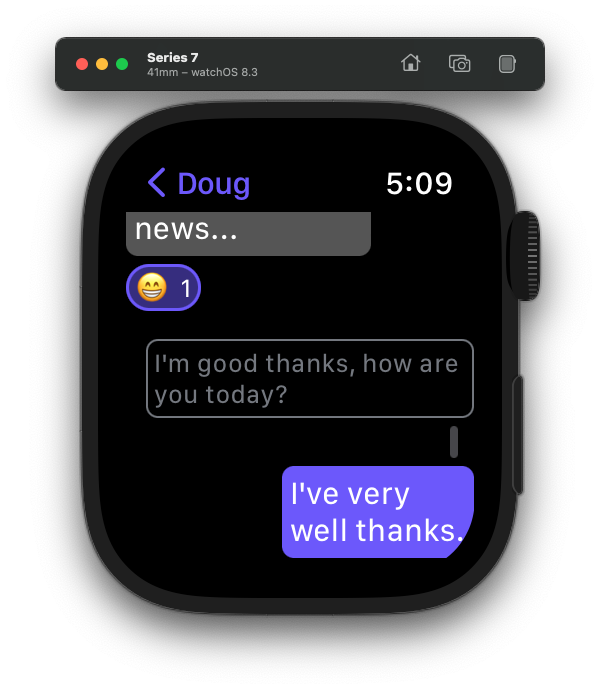

Threads

- Threaded Messaging is making forward progress on all 3 platforms; we’re aiming to help clear up cross-talk on the timeline by moving side-convo’s to the right panel. If you want to try it out, it's available in Labs on Web. We’ll be pushing Threads into Labs on Mobile in the next release!

Community Testing

- Join #element-community-testing:matrix.org to help out with the testing

- Coming up this week:

- The new search experience: Monday, 7th Feb at 15:30 UTC / 16:30 CET

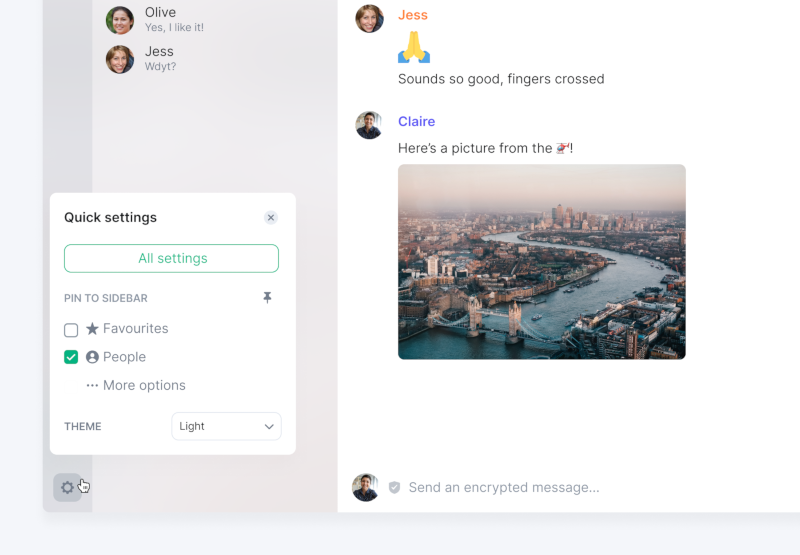

Element Web/Desktop (website)

Secure and independent communication, connected via Matrix. Come talk with us in #element-web:matrix.org!

Danielle says

- Bubbles are now available! Keeping your inbound messages on the left, and your outbound messages on the right your timeline should now be easier to skim read. This layout is off by default but to see it in action, update your Message Layout appearance preferences from Settings.

- Metaspaces have landed! Giving users a new way to display favourites, DMs and rooms outside of other spaces. Switch these on in Quick Settings at the bottom left of your app.

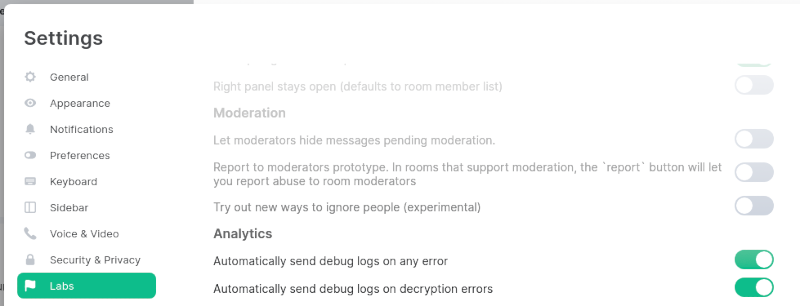

In Labs (Enable labs features in settings on develop.element.io or Nightly)

- New and improved Search!

- Provide feedback on your experience directly from the Search window.

- Threads, including design updates. The MSC is available hereMSC3440

Element iOS (website)

Secure and independent communication for iOS, connected via Matrix. Come talk with us in #element-ios:matrix.org!

Manu reports

- We’ve been working hard on improving the startup and resume times, you should start to see these in your app in 1.7.0.

- Work on a Rust prototype is underway. We’re excited to learn about the opportunities and advantages of this approach as we start to learn and experiment.

- Also, Xcode13 & iOS15 compatibility has been added for developers

- Coming soon in 1.8.0! Bubbles and an improved Onboarding experience

- Threads will also be hitting Labs on Mobile soon so let us know what you think.

Element Android (website)

Secure and independent communication for Android, connected via Matrix. Come talk with us in #element-android:matrix.org!

Danielle announces

- A hotfix (1.3.18) on Android will fix some bugs we found in this week’s release.

- Bubbles will also be landing soon, you can find this new feature in Settings > Preferences > Timeline. The feature has been merged to develop if you want to give it a try!

- Threads have also been merged on develop.

- We’ve been making improvements to the Onboarding experience for new users too.

In Labs

- Threads will soon be in Labs on Mobile. Switch it on and try it out!

Dept of Non Chat Clients 🎛️

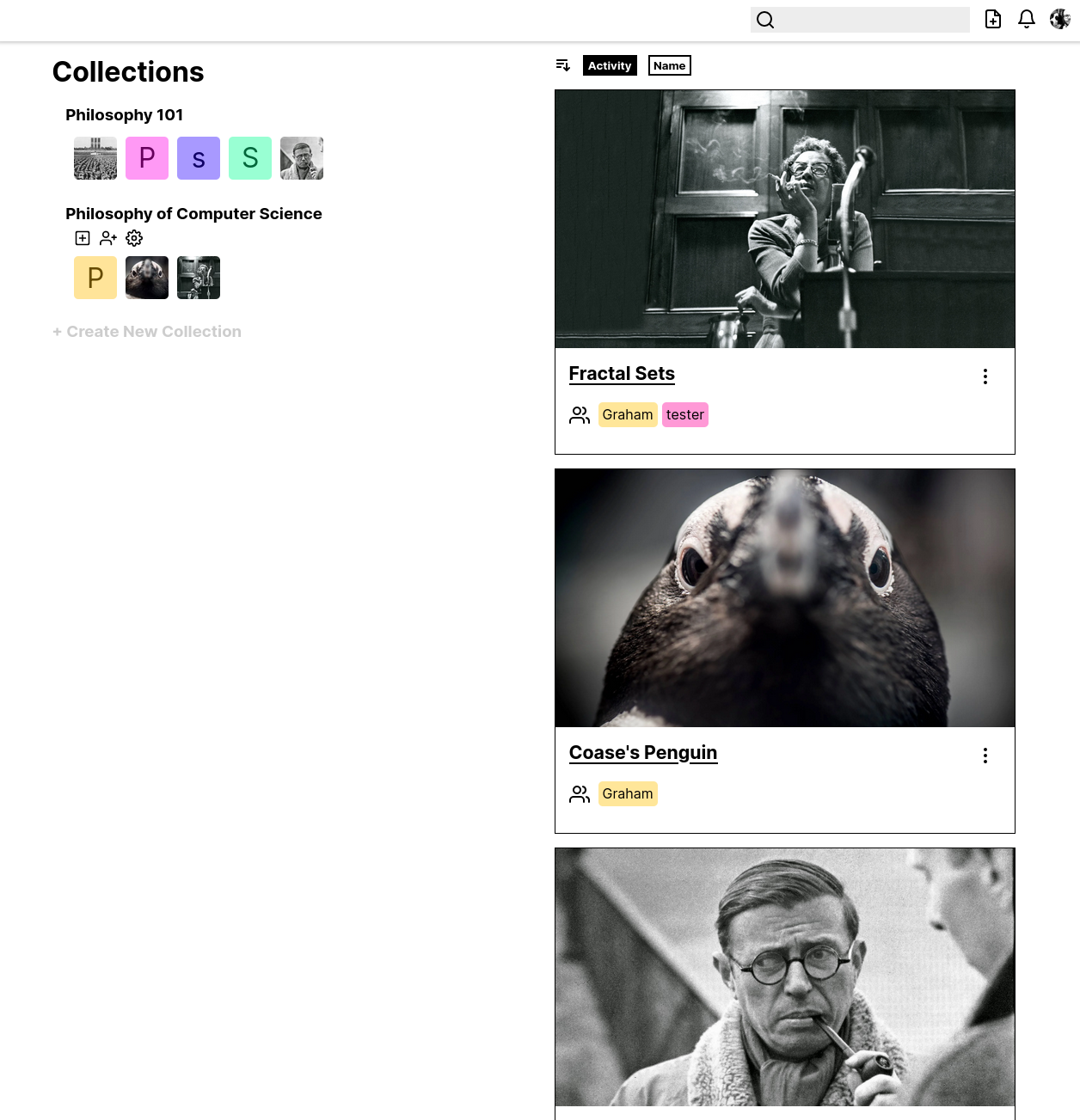

Populus Viewer (website)

A Social Annotation Tool Powered by Matrix

gleachkr says

Viewer Updates

Here's a big populus viewer update! Since last time, I've been mostly working on improving the user experience and onboarding for non-experts, as well as making my teaching-assistant bot a little smarter - this work is ongoing. But I have had time for a few new features 😁

- Populus now implements MSC3592 - Markup locations for PDF documents, a proposal building on MSC3574 - Marking up resources, so there's a documented format for interoperable PDF annotations (though this is not the final draft, see below!)

- I've reworked the sidebar for the PDF view, improving the aesthetics and allowing for a "fullscreen" view of PDF content.

- I've added user-directory search and improved the usability of the invite modal.

The reason that MSC3574 is not a final draft is that I'm increasingly looking at the w3c's web annotation data model as a compelling foundation for annotations on Matrix. Stay tuned for a upcoming MSC, or come over to #opentower:matrix.org to talk about the future of annotation on Matrix!

Populus-Philarchive

I've also been working on a proof-of-concept for one Matrix use-case that I'm hoping Populus can help fill. Social annotation can be a good tool for getting feedback on works in progress, or for discussing new research with your team or lab. Wouldn't it be nice if you could just pop open a paper on a preprint archive and start commenting, or say "hey friends, I'm reading this paper, what do you think?" And wouldn't it be nicer if you could do that and host the discussion on your university or team's Matrix server?

Here's a first pass at that idea: https://opentower.github.io/populus-philarchive/

At the moment works by just pasting in paper codes from philarchive.org - it'll preview bibliographic information and give you a list of discussions taking place around a given paper, with the option to create a new one. Sessions are shared with populus-viewer, and pdfs continue to be hosted by the original archive. There are a number of clear upgrade paths, by integrating with a preprint archive that has an open search API, or even by adding an OAI-PMH metadata harvester to the backend, to combine the metadata from a bunch of open paper archives. I'm really excited to see where this work goes.

nehko-krunner (website)

A KRunner plugin to list joined rooms and possibly other things from nheko.

LorenDB announces

I have been working on a little project over the last week: nheko-krunner. nheko-krunner is a KRunner plugin that loads rooms from nheko, displays them to the user, and allows the user to activate said rooms. How does it do this? Well, I've also been creating a D-Bus API for nheko! This code has not been merged yet, but once it is, you will be able to create your own plugins that access nheko via D-Bus!

The current functionality of nheko-krunner is simply (1) search and switch to rooms that you are in (not unlike the Ctrl-K switcher), and (2) join rooms from their aliases.

If you want to try out nheko-krunner, you will need to build from the

dbusbranch in my personal fork of nheko and then install nheko-krunner from the above repo.I hope that somebody finds this useful and I am excited to see what other D-Bus plugins may show up in the future!

Matrix Wrench (website)

Matrix Wrench is a web client to tweak Matrix rooms.

ChristianP announces

The versions 0.4.x brought improvements to the network log, letting you spot and investigate HTTP errors, bad JSON and network errors.

Ideally, I want to focus as much on the Matrix Spec as possible, but for the v0.5.0 I might venture into the territory of the Synapse Admin API, e.g. for listing and deleting media in a room. Please contact me, if you have use cases around media moderation you'd like me to consider.

export matrix messages (website)

A commandline utility to export matrix messages

Aine reports

emm (export matrix messages) v0.9.4 is here

Now you can ignore messages from some users, defined in the

-icli argument.For example, to ignore TWIM bot and me,

-i @twim:cadair.com,@aine:etke.cc

Dept of SDKs and Frameworks 🧰

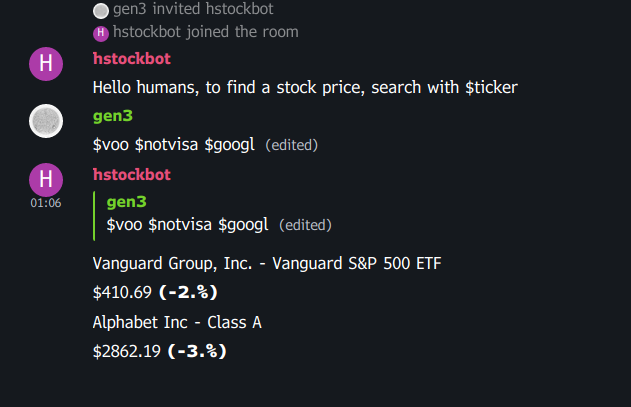

Halcyon (website)

Halcyon is an easy to use matrix library inspired by discord.py

gen3 announces

No new release this week. I've been working on the video sending functionality, and I am looking forward to seeing what that enables ya'll to do! In the meantime, I've published a template / demo bot you can find here: https://github.com/WesR/Halcyon-stock-bot . In just 37 lines of (unminified) code, this little bot:

- Sets a status message

- Automatically joins rooms via invite

- Searches messages for $stocks mentioned, then formats and replies the current price and daily percent change for all the tickers in the message Screenshot below

I'm always looking for more feedback, and love to see what people are working on. Come hangout in the Halcyon room: https://matrix.to/#/#halcyon:blackline.xyz Lastly, for more info at on the bot library visit https://github.com/WesR/Halcyon Happy Hacking!

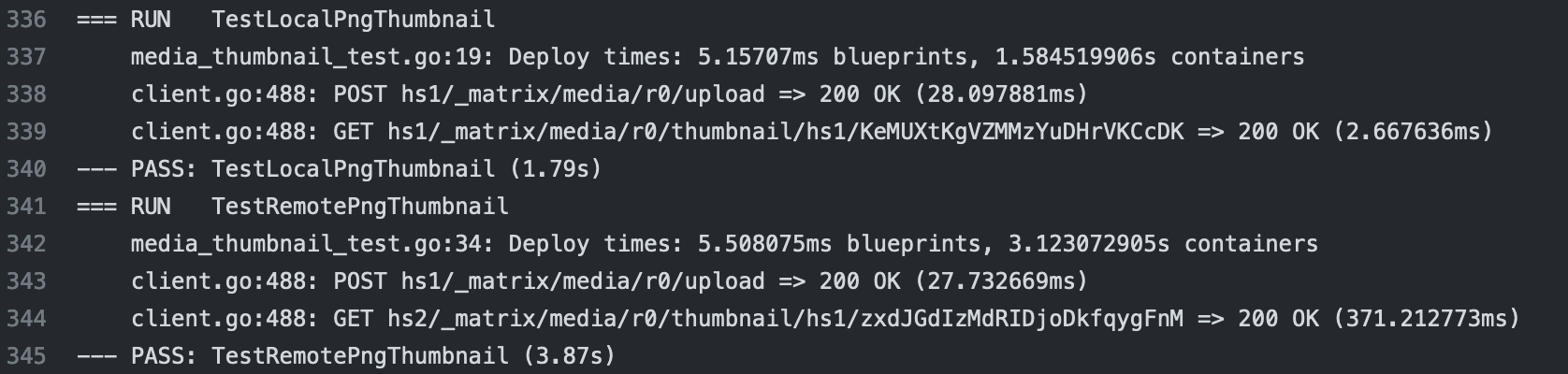

Polyjuice (website)

Elixir libraries related to the Matrix communications protocol.

uhoreg announces

The Polyjuice Project has a new component: Polyjuice Client Test, a tool for testing Matrix clients. Each test has its own preconfigured homeserver environment, implemented using the Polyjuice Server library, and can be customized according to the needs of the test. Only a few tests are implemented so far, but many more are planned, initially focusing on testing functionality related to end-to-end encryption. You can see a demo of it in the Matrix Live video.

Dept of Ops 🛠

matrix-docker-ansible-deploy (website)

Matrix server setup using Ansible and Docker

Slavi says

Thanks to HarHarLinks, matrix-docker-ansible-deploy can now install the matrix-hookshot bridge for bridging Matrix to multiple project management services, such as GitHub, GitLab and JIRA.

See our Setting up matrix-hookshot documentation to get started.

Matrix Corporal (website)

reconciliator and gateway for a managed Matrix server

Slavi says

matrix-corporal (as of version

2.2.3) is now published to Docker Hub (see devture/matrix-corporal) as a multi-arch container image with support for all these platforms:linux/amd64,linux/arm64/v8andlinux/arm/v7. Users on these ARM architectures no longer need to build matrix-corporal manually.

Dept of Bots 🤖

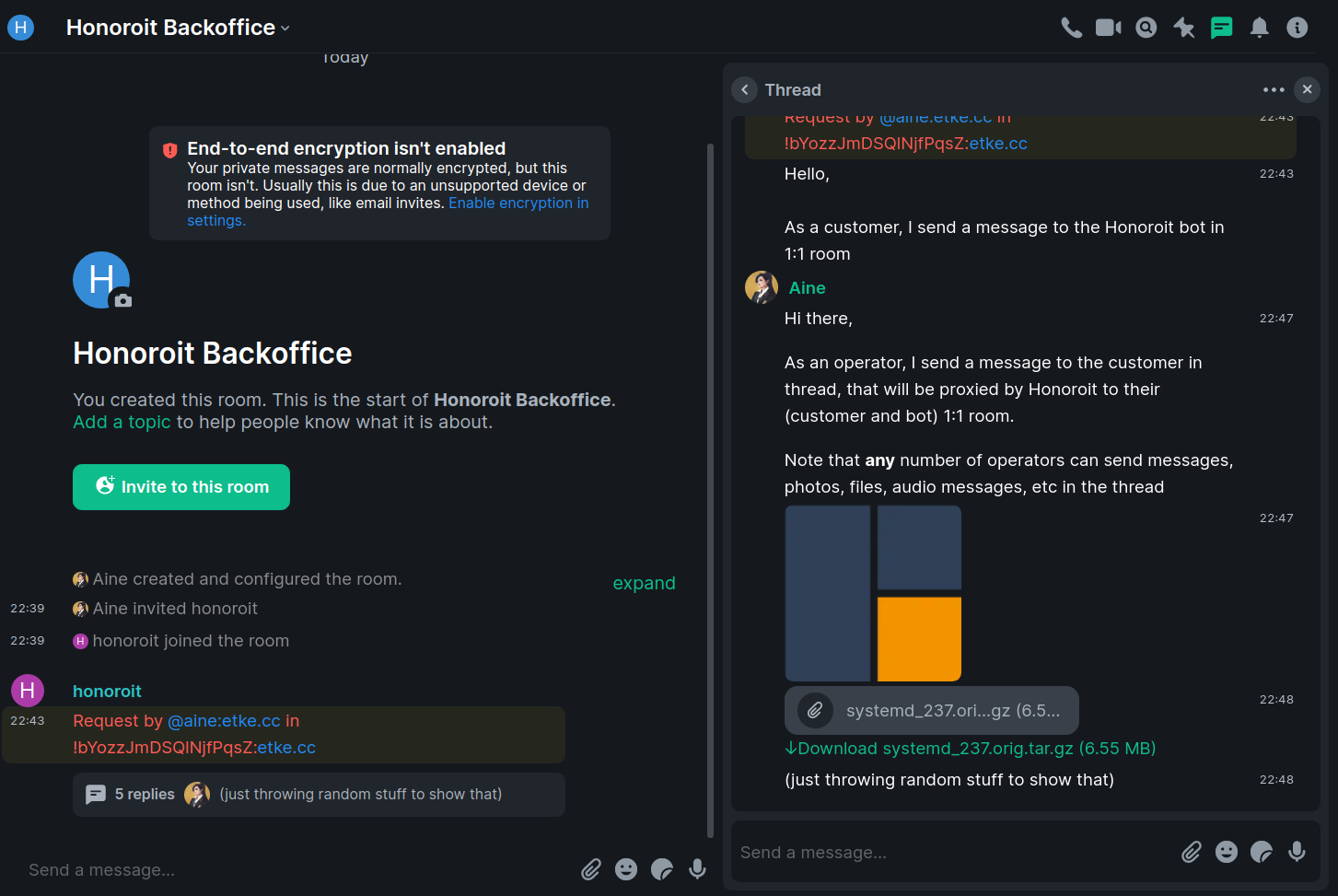

Honoroit (website)

A Matrix helpdesk bot

Aine announces

Honoroit v0.9.4 is here!

New version comes with in-memory caching for thread relations. It significantly decreases amount of requests to homeserver during thread relations solving, both for MSC3440 threads and reply-to chain fallback

Source code, say hi in #honoroit:etke.cc

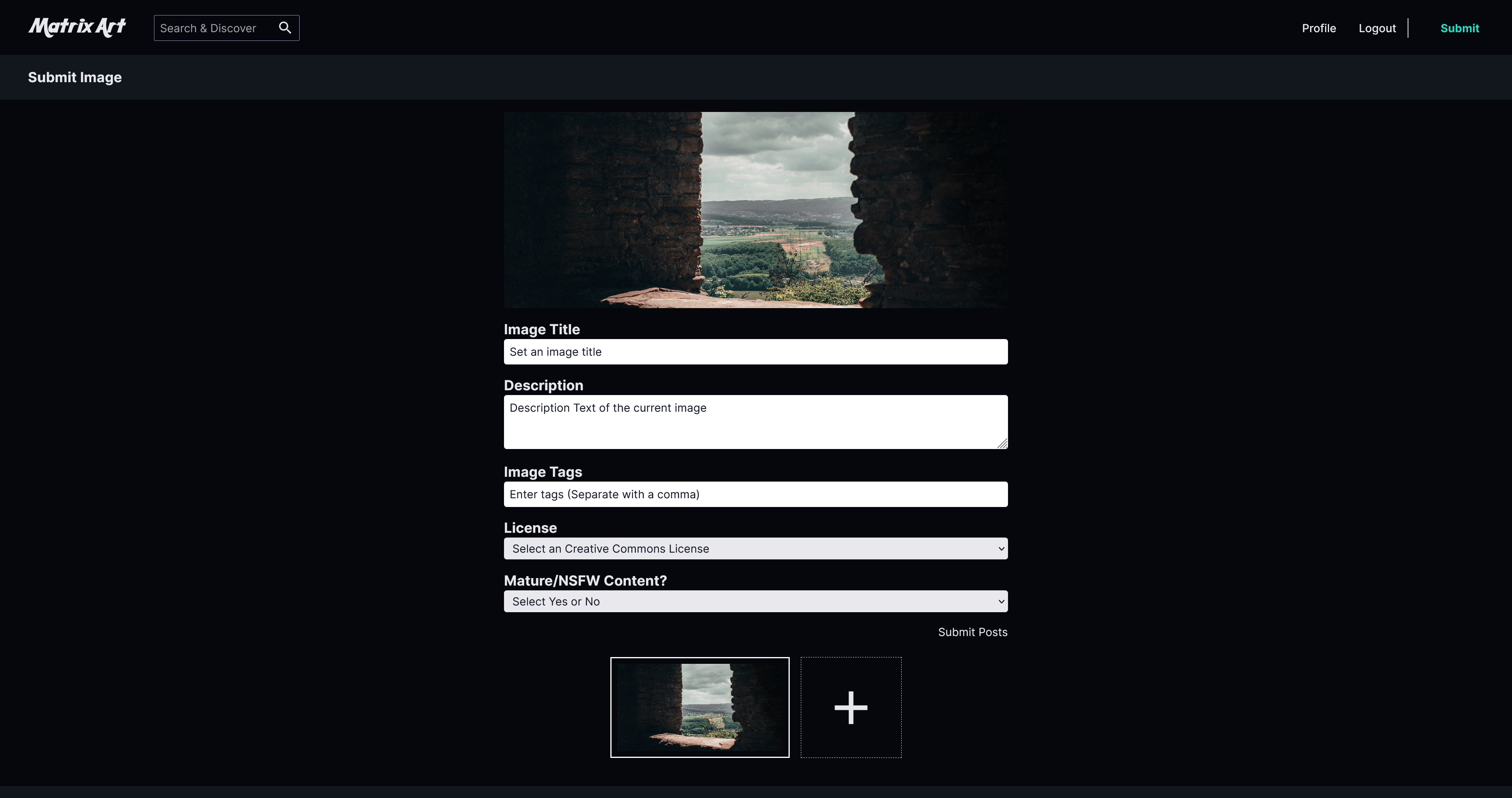

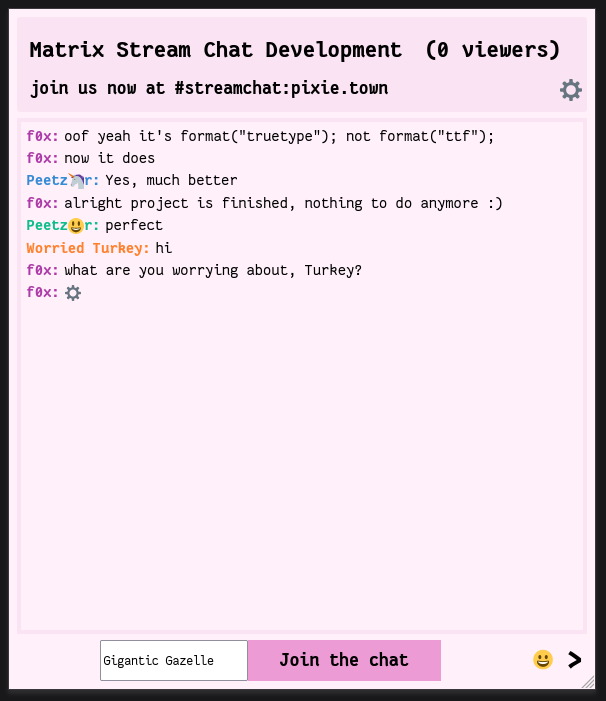

Dept of Social Media?

matrix-art (website)

A Deviantart Fork based on Matrix

MTRNord (they/them) says

This week the focus was on fixing quirks and making the profile (at least partially) editable and adding translations.

Changes

- Fonts now get hosted on the page itself due to the legal issues in Germany with Google Fonts hosted fonts

- Profile page has a rough UI to edit the profile page if logged in

- Licence gets now correctly displayed according to the Creative Commons Licence requirements

- Initial work on translations has started. A Weblate instance has been set up at https://trans.nordgedanken.dev for this.

- German translation was added

- Progress on the HS side to be able to use it as a public registration server for anyone who wants to post to Matrix Art. (yes, this really has a public registration HS)

- Mjölnir instance is set up which also is used to moderate Matrix Art in complete (Aka it is joining on creation.) This is used for being able to moderate the website.

- Errors are now properly reported to the user

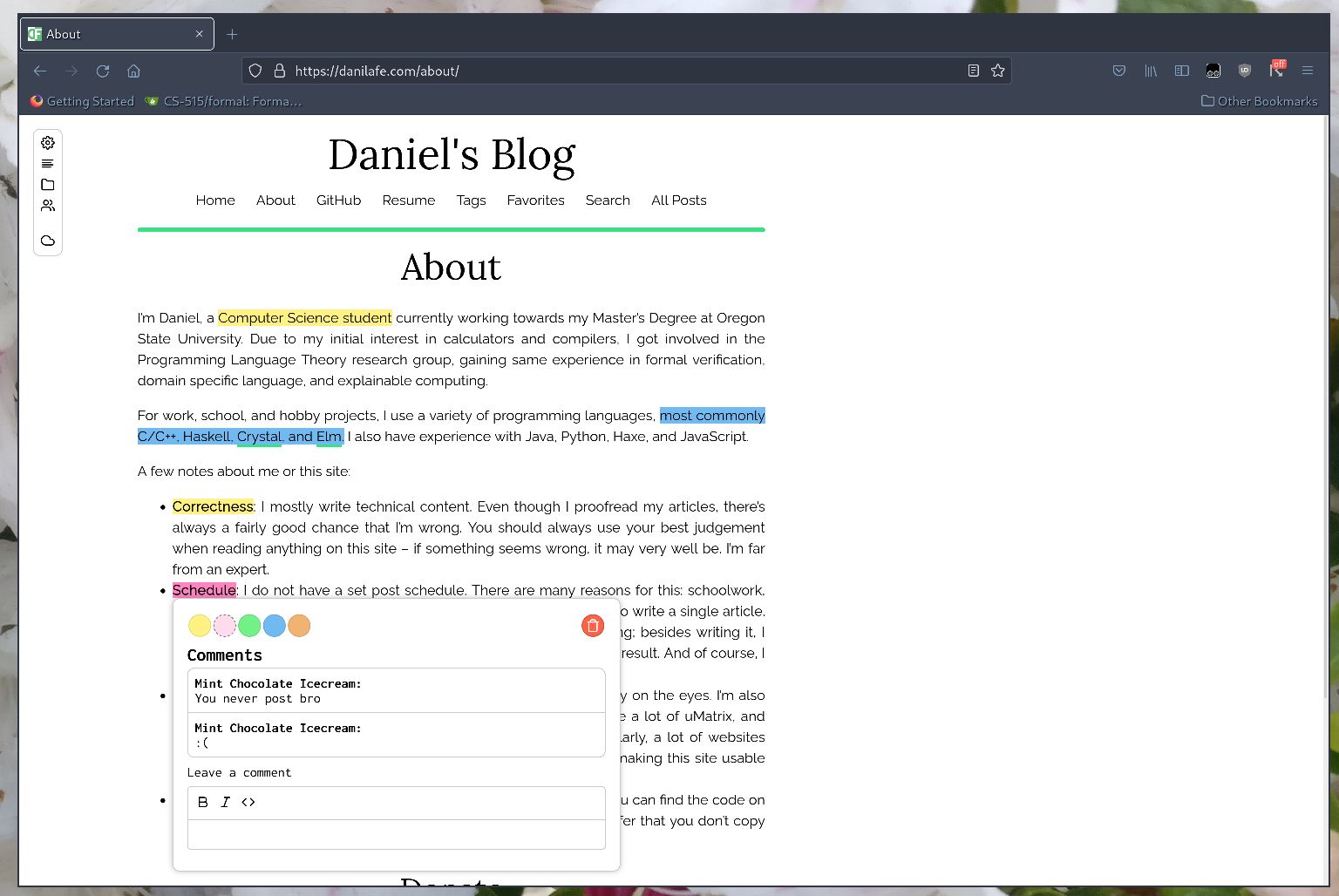

Dept of Interesting Projects 🛰️

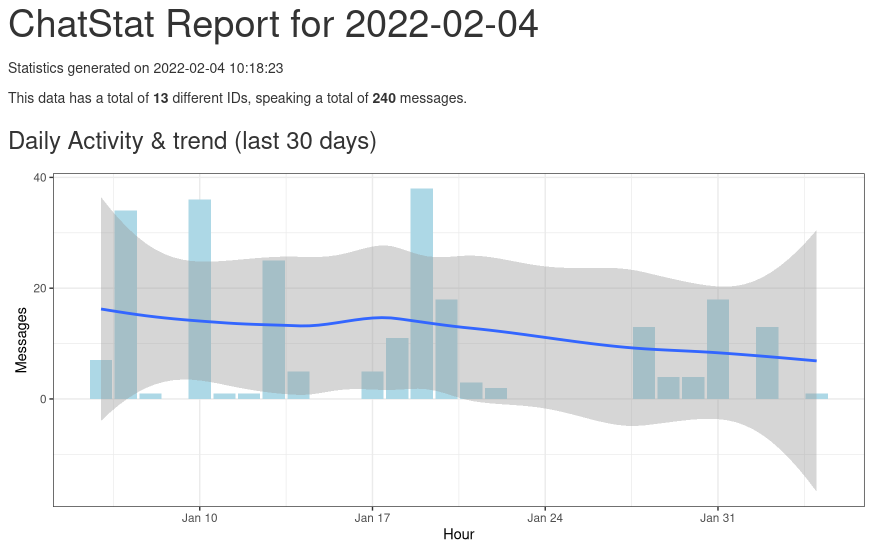

ChatStat (website)

An R package To Gather Stats From Chat Platforms

Gwmngilfen announces

ChatStat 0.1.0 release

ChatStat is an R package for making reports on Matrix rooms.

Ahead of my lightning talk on Sunday, ChatStat has been polished up and given it's first release. You can get it here. Huge thanks to @johrpan:johrpan.de for their contributions too.

The main highlight since my last TWIM is that we actually have report generation now! You can see an example here, or check the project wiki for an example of using the raw data with ggplot2 to make custom plots of your own.

If you do give it a try, please stop by #matrix-matrix_chat_stat:fosdem.org to let us know how you got on!

Matrix in the News 📰

Carl Schwan says

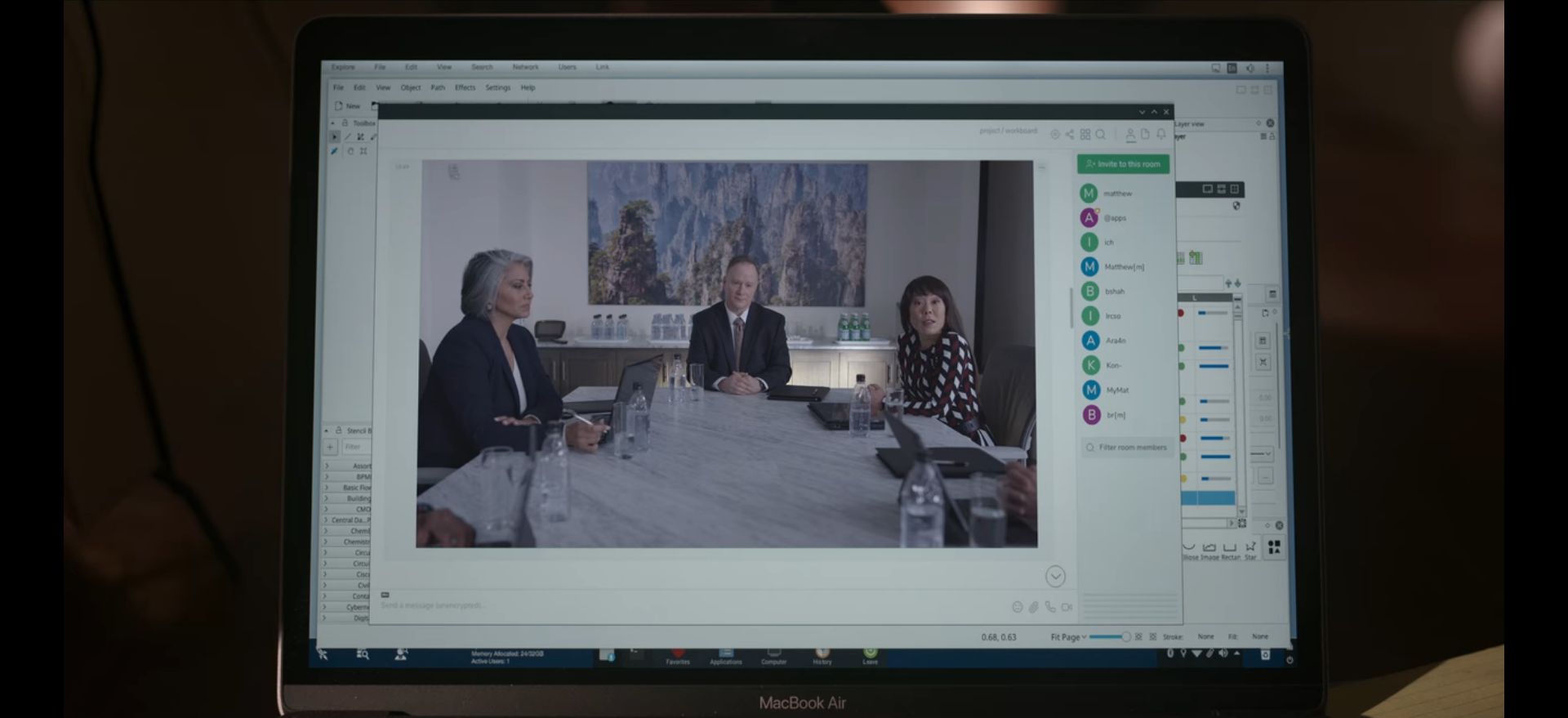

The season 2 of Raising Dion (a Netflix TV show) featured shortly a video call with Riot/Element and a few other open source software (e.g. Karbon). Oh and you might recognize a few usernames in the sidebar 😅

Moe (Moritz Dietz) announces

Circles has made it into a small German speaking Apple News site/App called ifun.de. „Circles-App: Neue alte Ideen für private soziale Netzwerke“ https://www.iphone-ticker.de/circles-app-neue-ideen-fuer-private-soziale-netzwerke-185764/ There wasn’t a mention of Matrix - which is kind of exciting really. This means it can just be the transparent layer of great apps :)

Dept of Ping 🏓

Here we reveal, rank, and applaud the homeservers with the lowest ping, as measured by pingbot, a maubot that you can host on your own server.

#ping:maunium.net

Join #ping:maunium.net to experience the fun live, and to find out how to add YOUR server to the game.

| Rank | Hostname | Median MS |

|---|---|---|

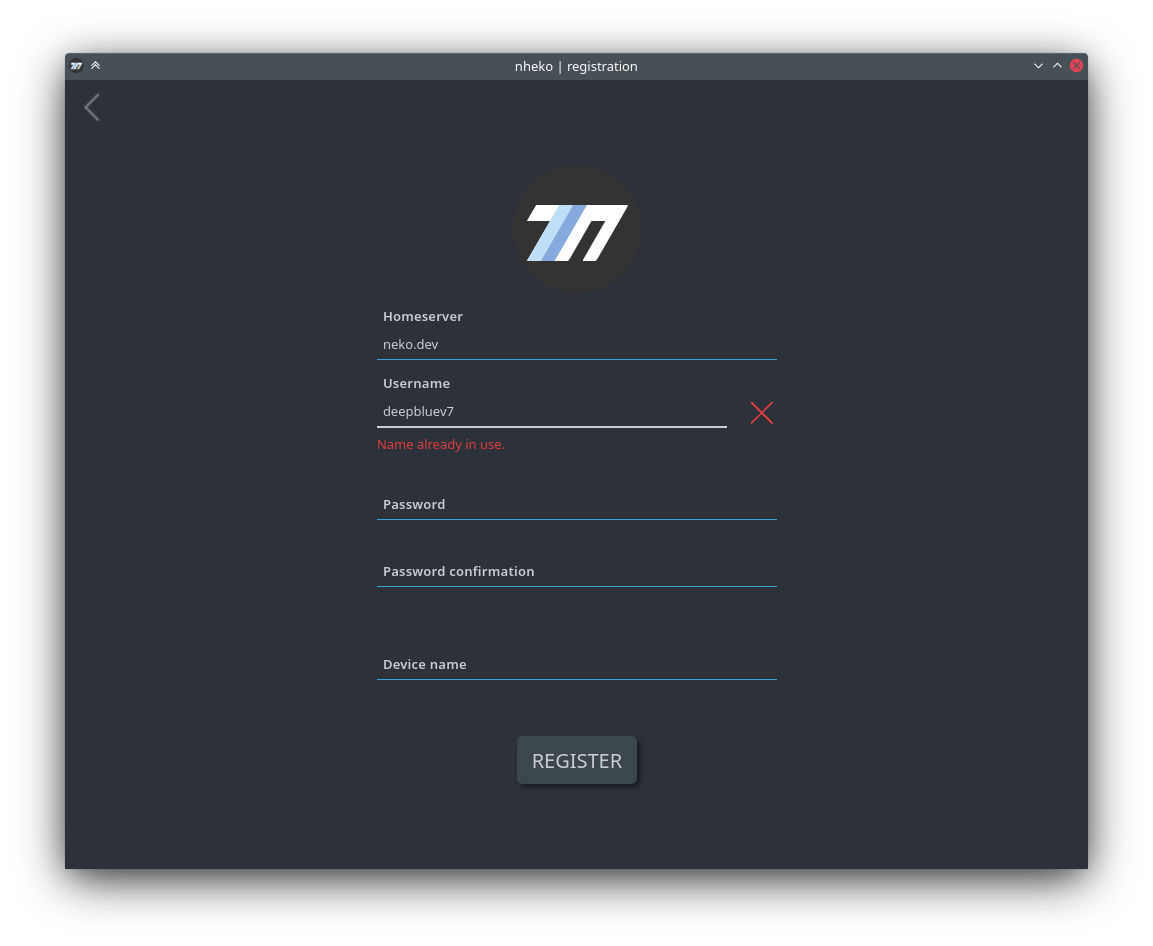

| 1 | neko.dev | 315 |

| 2 | envs.net | 579 |

| 3 | sosnowkadub.de | 822 |

| 4 | maescool.be | 1004.5 |

| 5 | aria-net.org | 1621 |

| 6 | utzutzutz.net | 1689 |

| 7 | rollyourown.xyz | 2247 |

| 8 | trygve.me | 2293.5 |

| 9 | midnightthoughts.space | 3045.5 |

| 10 | diasp.in | 3441 |

#ping-no-synapse:maunium.net

Join #ping-no-synapse:maunium.net to experience the fun live, and to find out how to add YOUR server to the game.

| Rank | Hostname | Median MS |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | rustybever.be | 899.5 |

| 2 | nognu.de | 947 |

| 3 | schuwi.science | 992 |

| 4 | conduit.cyberdi.sk | 1203.5 |

| 5 | dendrite01.fiksel.info | 1871 |

| 6 | dendrite.neilalexander.dev | 12309 |

That's all I know 🏁

See you next week, and be sure to stop by #twim:matrix.org with your updates!