Synapse 1.32.2 released

2021-04-22 — Releases — Dan CallahanSynapse 1.32.2 is out! Synapse now requires Python 3.6 (or later) and we've made a few small changes which you should be aware of before upgrading. These are documented in the upgrade notes.

Note: We scrubbed the releases of Synapse 1.32.0 and 1.32.1 as we discovered a pair of regressions including a bug with Prometheus metrics after tagging the release. These have been resolved.

On Monday, humankind flew a helicopter on Mars. And while our pursuit of Space(s) is considerably more modest, it is nevertheless progressing apace: Synapse 1.32 includes an experimental implementation of MSC3083.

This release also includes a new Synapse module for routing of presence updates, which can allow devices to share presence information without requiring that they also share a room. Please note there are some nuances to worker configuration when using this module which we hope to iron out in a future release.

The Admin API is newly able to manage rate limits, and the user listing endpoint can finally sort its results by a variety of criteria.

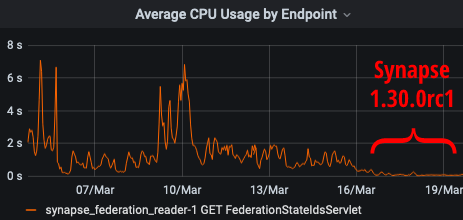

Otherwise, this is again a very internals-focused release: many additional type hints, improvements to structured logging, and small cleanups, especially those possible now that we've left Python 3.5 behind. We've made changes to how we check whether accounts are exempt from rate limits to avoid cases where we mistakenly applied limits to Application Services which should have been exempt, and we've fixed a bug with sharded federation senders which could occasionally pin the CPU.

See the Upgrading Instructions and Release Notes for further information.

🔗Thank You

Synapse is a Free and Open Source Software project, and we'd like to extend our thanks to everyone who contributed to this release, including dklimpel, languitar, ShadowJonathan, and xmunoz.