This is the third in a series of three posts which discuss recent work to improve type annotations in Sydent, the reference Matrix Identity server. Last time we discussed the mechanics of how we added type coverage. Now I want to reflect on how well we did. What information and guarantees did we gain from mypy? How could we track our progress and measure the effect of our work? And lastly, what other tools are out there apart from mypy?

🔗The best parts of --strict

While the primary goal was to improve Sydent's coverage and robustness, to some extent this was an experiment too. How much could we get out of typing and static analysis, if we really invested in thorough annotations? Sydent is a small project that would make for a good testbed! I decided my goal would be to get Sydent passing mypy under --strict mode. This is a command line option which turns on a number of extra checks (though not everything); it feels similar to passing -Wall -Wextra -Werror to gcc. It's a little extreme, but Sydent is a small project and this would be a good chance to see how hard it would be. In my view, the most useful options implied by strict mode were as follows.

🔗--check-untyped-defs

By default, mypy will only analyze the implementation of functions that are annotated. On the one hand, without annotations for inputs and the return type, it's going to be hard for mypy to thoroughly check the soundness of your function. On the other, it can still do good work with the type information it has from other sources. Mypy can

- infer the type of literals, e.g. deducing

x: strfromx = "hello"; - lookup the return types of standard library calls, via

typeshed; and similarly - lookup the return types of any annotated functions in your code or dependencies.

The information is already available for free: we may as well try to use it to spot problems.

🔗--disallow-untyped-defs and friends

This flag forces you to fully annotate every function. There are less extreme versions available, e.g. --disallow-incomplete-defs; but I think this is a good option to ensure full coverage of your module. It means you can rely on mypy's error output as a to-do list.

One downside to this: sometimes I felt like I was writing obvious boilerplate annotations, e.g.

def __str__(self) -> str:

...

There was one particular example of this that crops up a lot. Mypy has a special exception for a class's __init__ and __init_subclass__ methods. If a return type annotation is missing, it will assume these functions return None instead of Any. (See here for its implementation.) This is normally compatible with --disallow-untyped-defs and --disallow-incomplete-defs, with one exception. If your __init__ function takes no arguments other than self, mypy won't consider it annotated, and you'll need to write -> None explicitly.

It's also worth mentioning --disallow-untyped-calls, which will cause an error if an annotated function calls an unannotated function. Again, it helps to ensure that mypy has a complete picture of the types in your function's implementation. It also helps to highlight dependencies—if you see errors from this, it might be more practical to annotate the functions and modules it's calling first.

🔗--warn-return-any

If I've written a function and annotated it to return an int, mypy will rightly complain if its implementation actually goes on to return a str.

def foo() -> int:

# error: Incompatible return value type (got "str", expected "int")

return "hello"

If mypy isn't sure what type I'm returning though, i.e. if I'm returning an expression of type Any, then by default mypy will trust that we've done the right thing.

def i_promise_this_is_an_int():

return "hello"

def bar() -> int:

reveal_type(i_promise_this_is_an_int()) # Any

return i_promise_this_is_an_int()

Enabling --warn-return-any will disable this behaviour; to make this error pass we'll have to prove to mypy that i_promise_this_is_an_int() really is an int. Sometimes that will be the case, and an extra annotation will provide the necessary proof. At other times (like in this example), investigation will prove that there really is a bug!

🔗--strict-equality

This is a bit like a limited form of gcc's -Wtautological-compare. Mypy will report and reject equality tests between incompatible types. If mypy can spot that an equality is always False, there's a good chance of there being a bug in your program, or else an incorrect annotation.

I'm not sure how general this check is, since users can define their own types with their own rules for equality by overriding eq. Perhaps it only applies to built-in types?

🔗Quantifying coverage

It was important to have some way to numerically evaluate our efforts to improve type coverage. It's a fairly abstract piece of work: there's nothing user-visible about it, unless we happen to discover a bug and fix it.

The most obvious metric is the number of total errors reported by mypy. Before the recent sprint, we had roughly 600 errors total.

dmr on titan in sydent on HEAD (3dde3ad) via 🐍 v3.9.7 (env)

2021-11-08 12:35:37 ✔ $ mypy --strict sydent

Found 635 errors in 59 files (checked 78 source files)

This is a decent way to measure your progress when working on a particular module or package, but it's not perfect, because the errors aren't independent. Fixing one could fix another ten or reveal another twenty—the numeric value can be erratic.

🔗Reports

I found mypy's various reports to be a better approach here. There were three reports I found particularly useful.

🔗--html-report

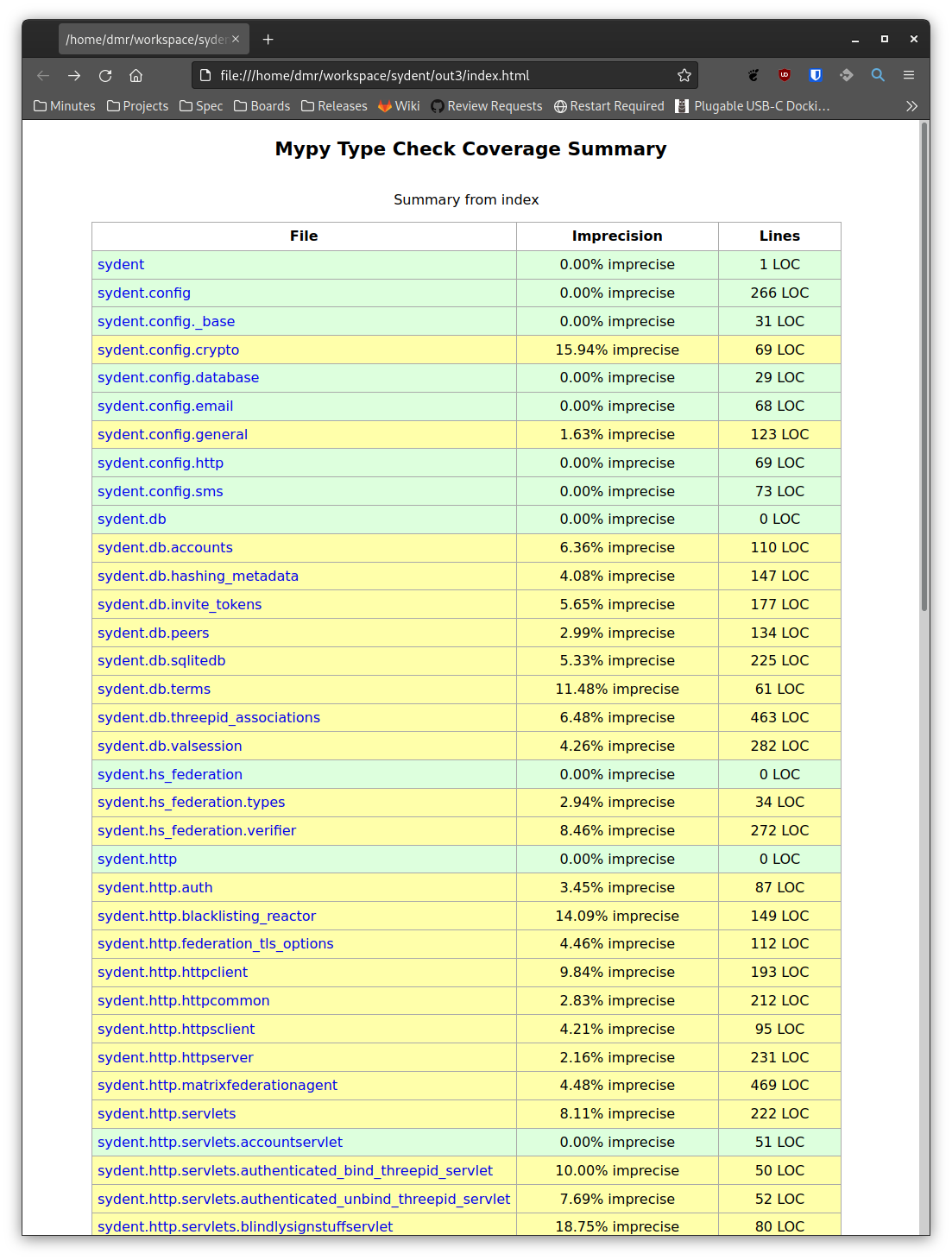

This produces a main index page showing the "imprecision" of each module. At the bottom of the table is a total imprecision value across the entire project.

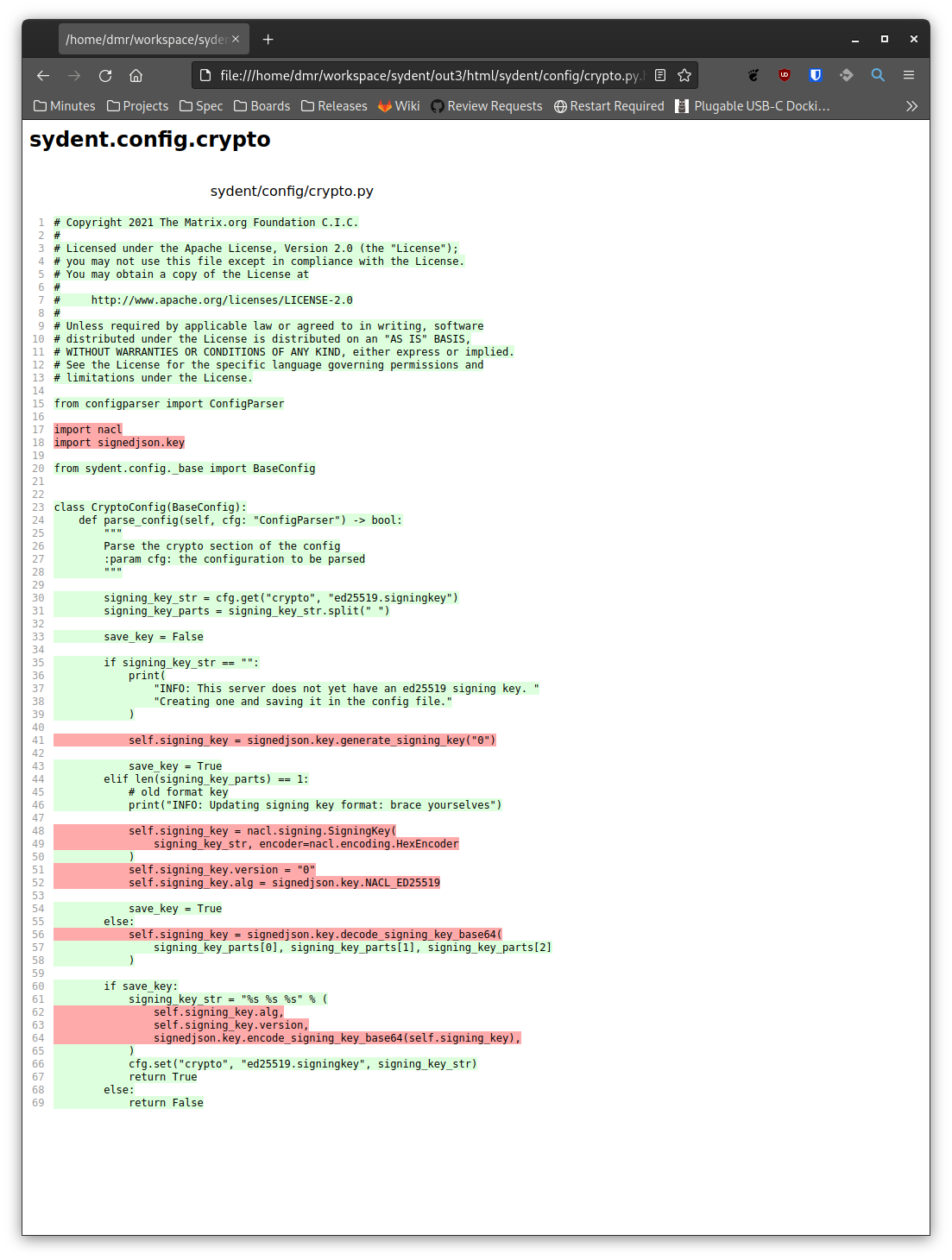

The precision for each module is broken down line-by-line and colour-coded accordingly, which is useful for getting an intuition for what makes a line imprecise. More on that shortly.

🔗--txt-report

This reproduces the index page from the html report as a plain text file. It's slightly easier to parse—that's how I got the data for the precision line graphs in part one of this series. That was a quick and dirty hack, though; a proper analysis of precision probably ought to read from the json or xml output formats. Here's a truncated sample:

+-----------------------------------+-------------------+----------+

| Module | Imprecision | Lines |

+-----------------------------------+-------------------+----------+

| sydent | 0.00% imprecise | 1 LOC |

| sydent.config | 0.00% imprecise | 266 LOC |

| sydent.config._base | 0.00% imprecise | 31 LOC |

| sydent.config.crypto | 15.94% imprecise | 69 LOC |

| ... | ... | ... |

| sydent.validators | 0.00% imprecise | 61 LOC |

| sydent.validators.common | 7.35% imprecise | 68 LOC |

| sydent.validators.emailvalidator | 1.30% imprecise | 154 LOC |

| sydent.validators.msisdnvalidator | 1.34% imprecise | 149 LOC |

+-----------------------------------+-------------------+----------+

| Total | 5.95% imprecise | 9707 LOC |

+-----------------------------------+-------------------+----------+

🔗--any-exprs-report

Selecting this option generate two reports: any-exprs.txt and types-of-anys.txt. The latter is interesting to understand where the Anys come from, but the former is more useful for quantifying the progress of typing. Another sample:

Name Anys Exprs Coverage

-------------------------------------------------

sydent 0 2 100.00%

sydent.config 0 185 100.00%

sydent.config._base 0 3 100.00%

sydent.config.crypto 34 80 57.50%

sydent.config.database 0 8 100.00%

sydent.config.email 0 86 100.00%

... ... ... ...

-------------------------------------------------

Total 544 11366 95.21%

The breakdown in types-of-anys.txt has more gory detail. I found the "Unimported" column particularly interesting: it lets us see how exposed we are to a lack of typing in our dependencies.

Name Unannotated Explicit Unimported Omitted Generics Error Special Form Implementation Artifact

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

sydent 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

sydent.config 0 3 0 0 0 0 0

sydent.config._base 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

... ... ... ... ... ... ... ...

sydent.util.versionstring 0 80 0 0 0 0 0

sydent.validators 0 4 0 0 0 0 0

sydent.validators.common 0 20 0 0 0 0 0

sydent.validators.emailvalidator 0 8 0 0 0 0 0

sydent.validators.msisdnvalidator 0 8 0 0 0 0 0

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Total 9 1276 273 0 37 0 17

🔗The meaning of precision

There are two metrics I chose to focus on:

- the proportion of "imprecise" lines across the project; I also used the complement,

precision = 100% - imprecision, and - the proportion of expressions whose type is not

Any.

These are plotted in the graph at the top of this writeup. I could see that precision and the proportion of typed expressions were correlated, but I didn't understand how they differed. I couldn't see an explanation in the mypy docs, so I went digging into the mypy source code. My understanding is as follows.

- There are five kinds of precision. Full details are visible in the

--lineprecision-report. - Two kinds of precision,

EMPTYandUNANALYZEDconvey no information, because there's nothing to analyze. - A line is marked as precise, imprecise or any based on the expressions it uses.

- An expression that has type

Anyleads to precisionANY. - I think an expression that involves

Anybut is notAnycounts as imprecise. For instance,Dict[str, Any]. - Remaining expressions have precision

PRECISE.

- An expression that has type

- A line's precision is the worst of all its expressions' precisions.

ANYis worse thanIMPRECISE, which is worse thanPRECISE.

The "imprecision" number reported by mypy counts the number of lines classified as IMPRECISE or ANY.

On balance, my preferred metric is the line-level (im)precision percentage. There wasn't much difference between the two in my experience, but the colour-coded visualisation in the HTML report is a neat feature to have. Maybe in the future there could be a version of the HTML report that colour-codes each expression?

🔗The larger typing ecosystem

There are plenty of articles out there about the typing. As well as the mypy blog itself, see Daniele Varrazzo's post on psycopg3 (2020), Dropbox's blog post (2019), Zulip's blog post (2016), Glyph's blog post on Protocols (2020) and a follow-up comparing them to zope.interface (2021) and Nylas's blog (2019). I'm sure there's plenty more out there.

It's worth highlighting the typeshed project, which maintains stubs for the standard library, plus popular third-party libraries. I submitted a PR to add a single type hint—it was a very pleasant experience! Microsoft has an incubator of sorts for stubs too.

🔗Other typecheckers

After the sprint to improve coverage, I spent a short amount of time trying the alternative type checkers out there. Mypy isn't the only typechecker out there—other companies have built and open-sourced their own tools, with different strengths, weaknesses and goals. This is by no means an authoritative, exhaustive survey—just my quick notes.

🔗Pyre (Facebook)

- I couldn't work out how to configure paths to resolve import errors; in the end, I wasn't able to process much of Sydent's source code.

- Couldn't get it to process annotations like

syd: "Sydent"where "Sydent" is an import guarded by TYPE_CHECKING. - No plugin system that I could see. That said, it has a separate mode/program for running "Taint Analysis" to spot security issues.

- Seemed stricter by default compared to mypy: there was less inference of types.

- Also has its own strict mode.

🔗Pyright (Microsoft)

-

Didn't seem to recognise

getLoggeras being imported fromlogging. Not sure what happened there—maybe something wrong with its bundled version oftypeshed? -

In a few places, Sydent uses

urllib.parse.quotebut only importsurllib. We must be unintentionally relying on our dependencies toimport urllib.parsesomewhere! Mypy didn't complain about this; pyright did. -

Seemed to give a better explanations of why complex types were incompatible. For example:

/home/dmr/workspace/sydent/sydent/replication/pusher.py /home/dmr/workspace/sydent/sydent/replication/pusher.py:77:16 - error: Expression of type "DeferredList" cannot be assigned to return type "Deferred[List[Tuple[bool, None]]]" TypeVar "_DeferredResultT@Deferred" is contravariant TypeVar "_T@list" is invariant Tuple entry 2 is incorrect type Type "None" cannot be assigned to type "_DeferredResultT@_DeferredListResultItemT" (reportGeneralTypeIssues) /home/dmr/workspace/sydent/sydent/sms/openmarket.py /home/dmr/workspace/sydent/sydent/sms/openmarket.py:93:13 - error: Argument of type "dict[_KT@dict, list[bytes]]" cannot be assigned to parameter "rawHeaders" of type "Mapping[AnyStr@__init__, Sequence[AnyStr@__init__]] | None" in function "__init__" Type "dict[_KT@dict, list[bytes]]" cannot be assigned to type "Mapping[AnyStr@__init__, Sequence[AnyStr@__init__]] | None" TypeVar "_KT@Mapping" is invariant Type "_KT@dict" is incompatible with constrained type variable "AnyStr" Type cannot be assigned to type "None" (reportGeneralTypeIssues)This would have been really helpful when interpreting mypy's error reports; I'd love to see something like it in mypy. Here's another example where I tried running against a Synapse file.

/home/dmr/workspace/synapse/synapse/storage/databases/main/cache.py /home/dmr/workspace/synapse/synapse/storage/databases/main/cache.py:103:53 - error: Expression of type "list[tuple[Unknown, Tuple[Unknown, ...]]]" cannot be assigned to declared type "List[Tuple[int, _CacheData]]" TypeVar "_T@list" is invariant Tuple entry 2 is incorrect type Tuple size mismatch; expected 3 but received indeterminate number (reportGeneralTypeIssues)This is really valuable information. It's worth considering Pyright as an option to get a second opinion!

-

It looks like Pyright's name for

AnyisUnknown. I think that does a better job of emphasising thatUnknownwon't be type checked. I'd certainly be more reluctant to typex: Unknownversusx: Any! -

Pyright is the machinery behind Pylance, which drives VS Code's Python extension. That alone probably makes it worthy of more eyes.

-

Seemed like it was the best-placed alternative typechecker to challenge mypy (the de-facto standard).

🔗Pytype (Google)

- Google internal? Seems to be maintained by one person semiregularly by "syncing" from Google.

- Apparently contains a script merge-pyi to annotate a source file given a stub file.

- No support for TypedDict: as soon as it saw one in Sydent, it stopped all analysis.

- No Python 3.10 support (according to the README anyway).

- I think it might use a different kind of typing semantics; its typing FAQ speaks of "descriptive typing" and a more lenient approach.

🔗PyCharm

PyCharm has its own means to typechecking code as you write it. It's definitely caught bugs before, and having the instant feedback as you type is really nice! I have seen it struggle with zope.interface and some uses of Generics though.

🔗Runtime uses of annotations

When annotations were first introduced, they were a generic means to associate Python objects with parts of a program. (It was only later that the community agreed that we really want to use them to annotate types). These annotations are available at runtime in the __annotations__ attribute. There's also a helper function in typing which will help resolve forward references.

>>> from typing import get_type_hints

>>> def foo(x: int) -> str: pass

...

>>> get_type_hints(foo)

{'x': <class 'int'>, 'return': <class 'str'>}

Programs and libraries are free to use these annotations at runtime as they see fit. The most well-known examples are probably dataclasses, attrs with auto_attribs=True and Pydantic. I'd be interested to learn if anyone else is consuming annotations at runtime!

🔗Summary

All in all, in a two-week sprint we were able to get Sydent's mypy coverage from a precision of 83% up to 94%. Our work would have spotted the bytes-versus-strings bug; we understand why the missing await wasn't detected. We fixed other small bugs too as part of the process. As well as fix bugs, I've hopefully made the source code clearer for future readers (but that one is hard to quantify).

There's room to spin out contributions upstream too. I submitted two PRs to twisted upstream; have started to work on annotations for pynacl in my spare time; and submitted a quick fix to typeshed.

Looking forward, I think we'd get a quick gain from ensuring that our smaller libraries (signedjson, canonicaljson) are annotated. We'll be sticking with mypy for now—the mypy-zope plugin is crucial given our reliance on twisted. We're also working to improve Sygnal and Synapse—though not to the extreme standard of --strict across everything.

I'd say the biggest outstanding hole is our processing of JSON objects. There's too much Dict[str, Any] flying around. The ideal for me would be to define dataclass or attr.s class C, and be able to deserialise a JSON object to C, including automatic (deep) type checking. Pydantic sounds really close to what we want, but I'm told it will by default gladly interpret the json string "42" as the Python integer 42, which isn't what we'd like. More investigation needed there. There are other avenues to explore too, like jsonschema-typed, typedload or attrs-strict.

To end, I'd like to add a few personal thoughts. Having types available in the source code is definitely A Good Thing. But there is a part of me that wonders if it might have been worth writing our projects in a language which incorporates types from day one. There are always trade-offs, of course: runtime performance, build times, iteration speed, ease of onboarding new contributors, ease of deployment, availability of libraries, ability to shoot yourself in the foot... the list goes on.

On a more upbeat note, adding typing is a great way to get familiar with new source code. It involves a mixture of reading, cross-referencing, deduction, analysis, all across a wide variety of files. It'd be a lot easier to type as you write from the get-go, but typing after the fact is still a worthy use of time and effort.

Many thanks for reading! If you've got any corrections, comments or queries, I'm available on Matrix at @dmrobertson:matrix.org.

The Foundation needs you

The Matrix.org Foundation is a non-profit and only relies on donations to operate. Its core mission is to maintain the Matrix Specification, but it does much more than that.

It maintains the matrix.org homeserver and hosts several bridges for free. It fights for our collective rights to digital privacy and dignity.

Support us